The terrorist attack at Pahalgam on April 22 changed everything. Twenty-six innocent tourists, segregated by religion and murdered in cold blood by Pakistan-based terrorists, triggered a chain of events that would fundamentally alter how we understand modern warfare in South Asia.

What followed – India’s Operation Sindoor on May 7 and Pakistan’s retaliatory Operation Bunyan-ul-Marsoos – wasn’t just another cross-border skirmish. It was the first real demonstration of network-centric warfare in our region, and frankly, it caught many of us off guard.

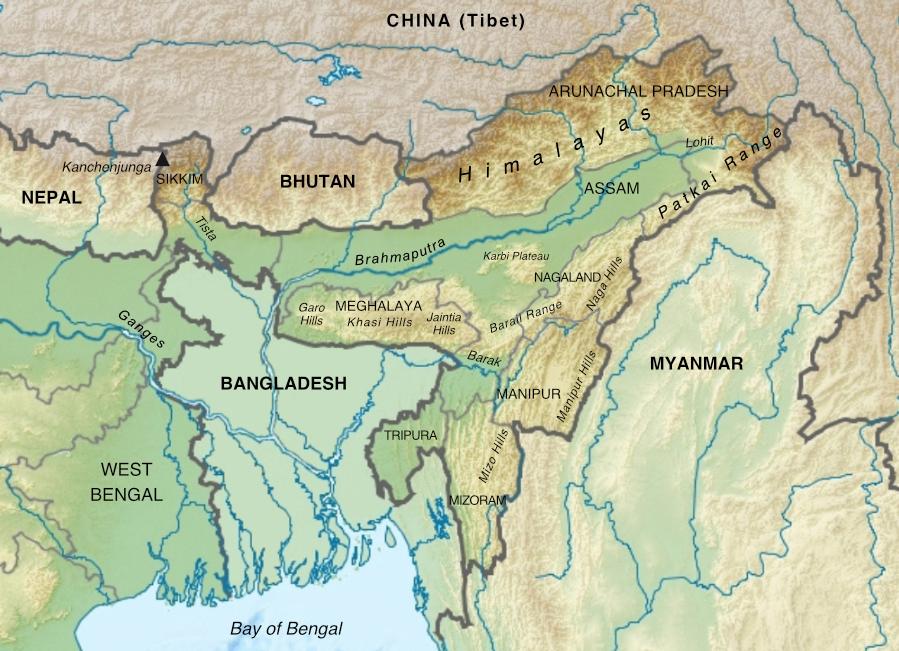

After almost four decades in uniform, including command assignments along both the line of control (LoC) and line of actual control (LAC), this author can attest that the May 2025 conflict represents a watershed moment. For the first time, we witnessed how advanced networking technologies could give a smaller military force significant tactical advantages against a conventionally superior adversary.

Read also: Beijing cannot dictate the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation

The New Battlefield: Network-Centric Warfare

To grasp what happened in May 2025, we must first understand network-centric warfare. Think of it as the difference between operating a traditional landline telephone system and today’s smartphones connected to the internet.

In conventional, platform-centric warfare, each tank, aircraft, or infantry unit operates somewhat independently. They rely on their own sensors, communicate through hierarchical channels, and make decisions based on limited information. It’s like fighting with walkie-talkies and paper maps.

Let this author take you back to how we used to fight wars. When this author was a young captain stationed along the western border during one of the country’s most high-profile and large-scale military exercises, warfare was refreshingly straightforward, if one can put it that way. You had your tanks, your artillery, your aircraft, and most importantly, you had brave soldiers operating these platforms.

Information? Well, that was a luxury that arrived in fits and starts. Sometimes through crackling radio transmissions that you could barely make out over the static. Sometimes via a dispatch rider-runner relay giving intelligence that was already 20 minutes old by the time it reached you. Decision-making moved up and down a chain of command that was as rigid as the Indian military’s ceremonial drills practised by the officers and soldiers every now and then.

Several years after the exercise just mentioned, this author remembers one particular night patrol along the LoC, where he spent three hours trying to coordinate with an artillery unit just eight kilometres away. By the time proper communication was established, the target had long since disappeared into the darkness. That’s just how things worked back then – and honestly, almost everyone in the military thought it was pretty sophisticated stuff.

Today, network-centric warfare transforms every military platform into a connected node in a vast digital network. Every soldier, every tank, every aircraft can instantly share what they see with everyone else. It’s like giving every unit a smartphone connected to a military version of Google Maps, WhatsApp, and YouTube combined.

The concept emerged from American military thinking in the late 1990s, articulated by Vice Admiral Arthur Cebrowski (retired), the founding director of the US defence department’s Office of Force Transformation (OFT), and John J Garstka, who was the chief technology officer in the US Joint Staff Directorate for Command, Control, Computer and Communications (C4) Systems before joining the OFT. They identified four fundamental principles: improved information sharing in networked forces leads to superior situational awareness, which enables better coordination, ultimately resulting in increased lethality, survivability, and operational speed.

Read also: Israel-Iran War – Tel Aviv’s tactical win, Iran’s strategic advantage

The Kill Chain Revolution

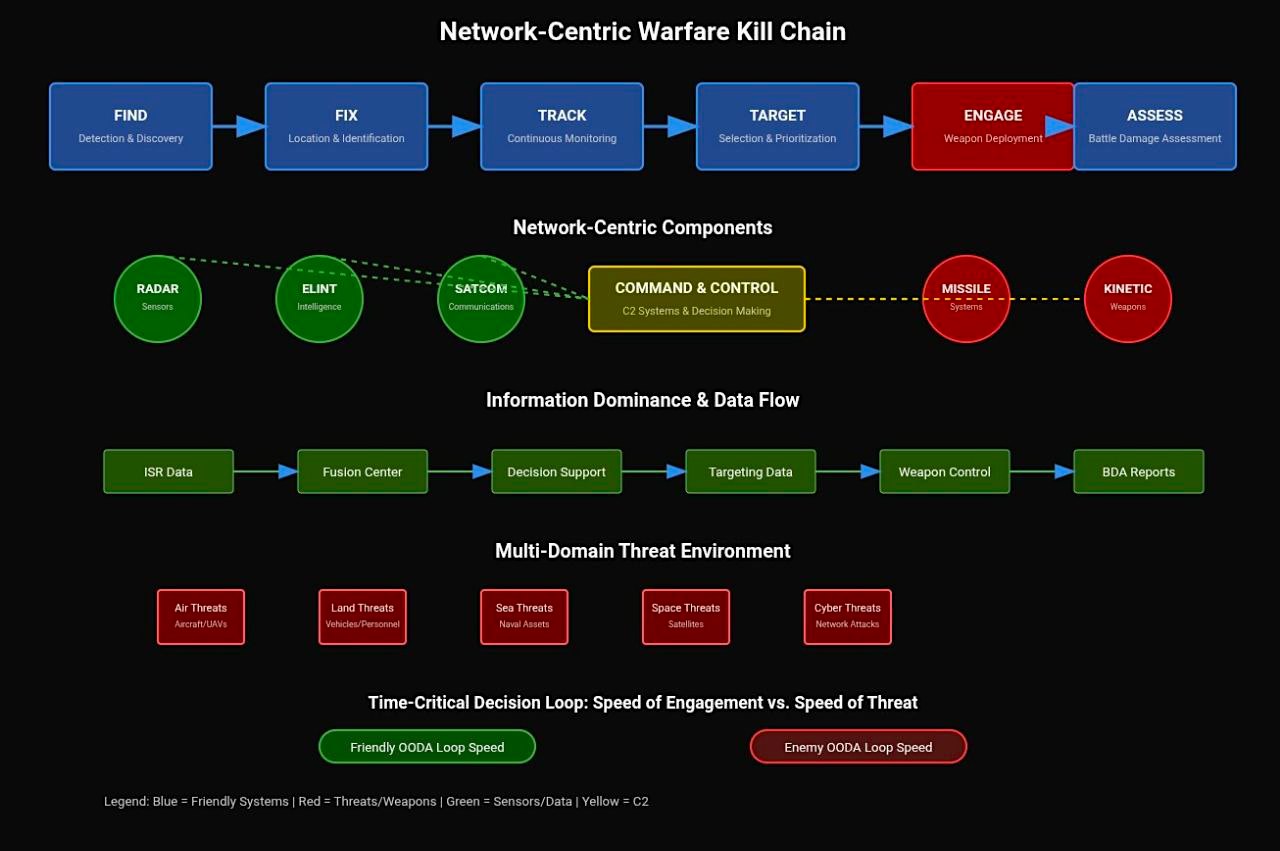

Central to network-centric warfare is the concept of the “kill chain” – the systematic process from identifying a target to destroying it. The military uses the F2T2EA model: find, fix, track, target, engage, and assess. In traditional warfare, this process could take hours or even days. A forward observer spots an enemy position, reports it through command channels, artillery coordinates are calculated, fire missions are planned, and finally, guns fire. Each step involves human decision-making and communication delays.

Network-centric warfare compresses this timeline dramatically. Automated systems can identify targets, calculate firing solutions, and engage within minutes or seconds. It’s the difference between sending a telegram and sending an instant message.

This compression happens through what military theorists call the OODA loop – observe, orient, decide, act. Colonel John Boyd, former US Air Force fighter pilot and military strategist, first developed this concept. He argued that whoever completes their OODA loop faster gains decisive advantage.

So, network-centric warfare accelerates your OODA loop while disrupting your enemy’s.

Read also: With FM Munir in Pak’s charge, India must see the ‘black swan’ coming

Pakistan’s Surprise Advantage

When Pakistan launched Operation Bunyan-ul-Marsoos (meaning “solid wall of lead” in Arabic), they demonstrated network-centric capabilities that surprised military analysts worldwide. The operation’s very name reflected Pakistan’s confidence in their integrated systems.

How did Pakistan achieve this capability? The answer lies in Chinese integration. Over the past decade, Pakistan has quietly integrated Chinese network-centric technologies across their military. Chinese J-10C fighters with PL-15 beyond-visual-range missiles, HQ-9 air-defence systems, and sophisticated electronic warfare capabilities now operate within a unified Pakistani-Chinese network.

During the conflict, China provided Pakistan real-time intelligence through the BeiDou satellite system and advanced radar networks. Pakistani forces could track Indian aircraft movements and coordinate defensive responses with unprecedented precision.

This author witnessed similar Chinese technological integration during border-personnel meetings (BPMs). The sophistication of Pakistan’s sensor-fusion capabilities – integrating Swedish SAAB 2000 Erieye early-warning aircraft with Chinese combat platforms – created comprehensive air-situation awareness that matched anything we possessed.

Pakistan demonstrated compressed decision cycles, operating within India’s OODA loop. They achieved multi-domain coordination across air, land, and cyber domains simultaneously. Most concerning, they integrated kinetic operations with cyberattacks, targeting over 1.5 million Indian digital infrastructure components. And soon, we are going to witness the integration and dominance of China-Pakistan collaboration across six domains – air, land, sea, cyber, space, electromagnetic spectrum.

Read also: India mustn’t take Pakistan COAS’s promotion to field marshal lightly

India’s Network-Centric Progress

India hasn’t been idle in developing network-centric capabilities. The Air Force Network (Afnet), commissioned in September 2010, replaced 1950s-era troposcatter technology with nationwide fibre-optic communications. The Afnet serves as the backbone for the Integrated Air Command and Control System (IACCS), which performed effectively during Operation Sindoor.

The Defence Communication Network (DCN) – a ₹600 crore triservice system designed by HCL – covers 57,000 kilometres of fibre-optic cable connecting major military installations. It represents the single-largest satellite-connected terrestrial network in the Indian armed forces.

During Operation Sindoor, these systems demonstrated their worth. IACCS coordinated India’s layered air defence, integrating sensors from all three services to intercept Pakistani drones and missiles. The system’s multilayered sensors and indigenous counter-UAV capabilities proved effective.

Critical Gaps Exposed

However, the May 2025 conflict exposed serious limitations in India’s network-centric development. Having served in various command positions, this author can identify several critical shortcomings. Some of them are:

Inter-service integration remains problematic – Each service operates separate networks lacking seamless interoperability. The Army, Navy, and Air Force can communicate, but they don’t truly share information in real-time. This fragmentation prevents the rapid information sharing essential for effective network-centric operations.

Battlefield-management systems have dangerous gaps – While Army headquarters can access satellite imagery and intelligence about developments along the LAC, frontline troops cannot receive this information in real-time. These intelligence assets remain available only to higher headquarters located kilometres behind the front lines.

Unlike China’s “Qu Dian” system or Pakistan’s developing “Rehbar” battlefield-management system, India lacks comprehensive tactical-level network integration. This prevents the rapid information dissemination essential for compressed kill-chain operations.

Technological dependencies create vulnerabilities – India’s network-centric systems rely heavily on foreign components and software. Recent incidents involving hacked Indian military drones revealed Chinese components containing potential backdoors for remote exploitation. During critical operations, such dependencies can enable adversaries to disrupt our kill chain.

Read also: Threat of China annexing Tawang is real. What must India do?

The China-Pakistan Challenge

The May 2025 conflict revealed a fundamental shift in the threat environment. The traditional “two-front war” scenario has evolved into what strategic analyst Pravin Sawhney termed as “one-front reinforced” challenge – China directly supporting Pakistan with real-time intelligence, advanced weapons integration, and cyberwarfare coordination.

This represents more than tactical cooperation. It’s strategic integration that fundamentally alters regional balance-of-power calculations. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has created economic dependencies, but the military integration demonstrated in May 2025 shows how these economic ties translate into operational advantages.

Let’s take the China-Pakistan fibre-optic cable project, for example. The project currently under development represents a significant enhancement to regional communication infrastructure, which establishes a crucial terrestrial link for data transmission across one of the world’s most strategically important corridors. This ambitious undertaking forms an integral component of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), itself a flagship initiative within China’s broader BRI programme.

The project encompasses the installation of 820 kilometres of advanced fibre-optic cabling along the historic Karakoram Highway, stretching from Rawalpindi in Pakistan’s Punjab province to the Khunjerab pass – the world’s highest paved international border crossing at 4,693 metres above sea level, linking to nodes in Xinjiang and Tibet that connect to China’s Western Theatre Command headquarters in faraway Chengdu, in Sichuan province. This terrestrial link promises to dramatically improve Pakistan’s international connectivity while providing direct digital access to China and the Central Asian republics, potentially reducing Pakistan’s dependence on vulnerable undersea cables that currently carry the majority of its international internet traffic.

While proponents herald this infrastructure as an essential catalyst for accelerated economic activity and enhanced operational efficiency across the region, the project’s strategic military implications warrant considerable attention and cannot be understated. The establishment of such comprehensive cutting-edge high-speed digital infrastructure linking Pakistan’s military headquarters to China’s India-centric Western Theatre Command along this sensitive border region – historically contested and of immense geopolitical significance – raises serious questions about dual-use capabilities and potential intelligence-gathering applications.

The Karakoram Highway itself has long served as a critical supply route and strategic asset, and the addition of sophisticated communication infrastructure could fundamentally alter the regional balance of power, particularly given the ongoing tensions with India and the broader great power competition between China and the United States in South Asia.

From this author’s experience monitoring Chinese activities along the northern borders, their approach to network-centric warfare is methodical and comprehensive. They don’t just provide equipment; they create integrated systems that function as unified networks across multiple countries.

Read also: India @ 75 – New Delhi’s security challenges and path forward

The Reform Imperative

The Ministry of Defence’s declaration of 2025 as the “Year of Reforms” couldn’t be more timely. The May conflict has provided both warning and roadmap for essential changes. Some are:

Formulation and implementation of the National Security Strategy (NSS) – India lacks a publicly released comprehensive NSS despite previous attempts. The government must urgently formulate and release one with clearly defined security doctrines, including adaptation strategies for evolving threats like network-centric warfare. The document should outline short, medium, and long-term strategies to counter information warfare and various forms of cyberwarfare, emphasizing indigenous social media platforms, smart applications, and India-based data centres. China’s ban on western social media platforms and services demonstrates the importance of preventing potential surveillance exploitation.

Integrated Theatre Commands must be prioritized – The proposed structure – China-focused Northern Command, Pakistan-focused Western Command, and Maritime Theatre Command – would enable unified responses to reinforced threats. Service-specific resistance to this integration must be overcome.

Advanced technology integration requires acceleration – Artificial intelligence, machine learning, hypersonic technologies, and robotics must be rapidly incorporated into military operations. The transition from “network-centric” to “data-centric” warfare demands sophisticated AI-enabled systems for real-time decision support.

Indigenous capability development is crucial – Reducing dependence on foreign technology components represents a critical security imperative. Defence industrial corridors and “Atmanirbhar Bharat” initiatives must prioritize indigenous alternatives to Chinese and other foreign systems.

Practical Solutions

Based on operational experience, this author recommends several immediate measures:

* Develop comprehensive battlefield management systems providing real-time information sharing from strategic headquarters to tactical units. Current sensor-to-shooter gaps must be eliminated through integrated networks that reach frontline troops.

* Enhance cyberwarfare capabilities significantly. The Defence Cyber Agency, established in 2019 with only 1,000 personnel, represents insufficient response to China’s extensive cyberwarfare infrastructure. We need indigenous cyber weapons and comprehensive cyber resilience frameworks.

* Integrate cyber and electronic warfare under unified commands, following China’s Strategic Support Force model. This integration would enable coordinated information warfare operations across multiple domains.

* Accelerate satellite and space-based asset development. Indigenous satellite navigation, communications, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities will reduce foreign dependence while providing comprehensive battlespace awareness.

Read also: Understanding Pakistan’s ‘deep state’ and its threat to world

The Path Forward

The May 2025 conflict has fundamentally altered South Asian military dynamics. Pakistan’s successful integration of Chinese network-centric technologies created a reinforced threat that challenges India’s conventional military superiority.

Network-centric warfare represents comprehensive transformation in military thinking, not mere technological upgrade. Pakistan’s ability to compress kill-chain timelines, achieve multi-domain coordination, and maintain information superiority through Chinese support demonstrates decisive advantages available to smaller forces facing conventionally superior adversaries.

For India, the conflict exposed vulnerabilities requiring urgent reform. Fragmented service-specific networks create exploitable gaps that sophisticated adversaries can leverage. Success in addressing these challenges depends on overcoming bureaucratic resistance, accelerating indigenous technology development, and achieving genuine triservice integration.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. Failure to adapt to network-centric warfare realities risks strategic marginalization. Successful transformation could establish India as a leading military power capable of deterring 21st-century threats.

After decades in uniform, this author has witnessed numerous technological transitions. The May 2025 conflict represents the most significant military evolution since the introduction of precision-guided munitions. How India responds will determine not only immediate security posture but long-term regional power status.

The warning has been delivered. The roadmap is clear. Now comes the hard work of implementation.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect the views of India Sentinels.

Follow us on social media for quick updates, new photos, videos, and more.

X: https://twitter.com/indiasentinels

Facebook: https://facebook.com/indiasentinels

Instagram: https://instagram.com/indiasentinels

YouTube: https://youtube.com/indiasentinels

© India Sentinels 2025-26