Indian Army soldiers atop a figure after reclaiming a Pakistani-occupied height in Kargil.

Indian Army soldiers atop a figure after reclaiming a Pakistani-occupied height in Kargil.

Hot LoC: Did ‘Kargil’ Ever End?

History is more darkness than light

The history books went to sleep after the declaration of “victory” on July 26, 1999. But did the “war” end? Did it end “successfully”? Did we expel the Pakistani forces (Northern Light Infantry troops and other irregular combatants) from all the peaks they had encroached upon and occupied? Did we restore status quo ante and get a good deal on the ceasefire?

We hear about highly publicized actions on the LoC (line of control) – the de facto India-Pakistan border in Kashmir, the raids, the artillery exchanges and the never-ending caravan of body bags, as more and more soldiers fell to the perpetual blood-letting. And we never get to hear some stories that ought to be told and heard. We, at India Sentinels, will continue with our endeavour to bring to you our unsung heroes, whose stories lie buried in snow, dust or sand.

The charioteers of history

Lieutenant Colonel Anil Duhoon (retired) was commissioned on June 11, 1988, in 14 Mahar Regiment of the Indian Army. The unit was at Ferozepur, Punjab at that time. His commissioning date coincides with that of his father’s. His father had got relegated in the academy and he too lost a term. So he had started his career according to the family tradition.

Col Duhoon had a rather eventful career with the Indian Army. He served at a time when, going by the current narrative in the country, our armed forces lived a rather tame existence – when our men in uniform were supposedly fettered by the governments of the day. Each of those “eventful” episodes involving our “Rambo Duhoon” merits separate stories in our series on the Indian armed forces. Today we will live through his eyes, that crimson day in 2002 when the white snow turned red – in the Batalik heights.

Lt Col (then-Major) Anil Duhoon at the time of his posting in Batalik.

Lt Col (then-Major) Anil Duhoon at the time of his posting in Batalik.

In the year 2001, (then) Major Duhoon was in the medical category “A2 Permanent” after a second knee surgery for reconstructing the ligaments. Considering his medical status, he was posted out of the unit to a peace location. His unit,14 Mahar, moved to Batalik subsector in Kargil as a part of the 192 Brigade. Being the “Rambo” that he was, he wouldn’t pass up this opportunity and took up the case with Army Headquarters and volunteered to go with the unit, despite not being in the right medical category. AHQ obliged and he was sent up.

The brigade commander at that time was Brigadier Harcharanjit Singh Panag (who later rose to the rank of lieutenant general and served as the general officer commanding in chief of the Northern Command and, later, Central Command). He was initially sceptical. “Tu langda yahan pe kya karega? (Lame guy, what will you do here?)”

Then-Northern Army commander Lt Gen HS Panag salutes at a war memorial during a wreath-laying ceremony on“Vijay Diwas” (“Victory Day”) commemoration in Drass, Kargil sector, on July 26, 2007.

Then-Northern Army commander Lt Gen HS Panag salutes at a war memorial during a wreath-laying ceremony on“Vijay Diwas” (“Victory Day”) commemoration in Drass, Kargil sector, on July 26, 2007.

Maj Duhoon assured him that he has come with the intention of serving right at the front with his company and not to hang around in the rear areas. Seeing Maj Duhoon’s confidence, Brigadier Panag personally ascertained that the major had actually reached his company headquarters atop Point 5156.

Watch on the LoC

As a company commander, Major Duhoon was deployed at a hilltop feature known as Point 5156, which was one of the most sensitive posts in the (XIV) Corps zone, and a substantive major on the post was a mandatory requirement. Any movement during daytime would attract immediate fire from enemy side and vice versa. The enemy post opposite Point 5156 was at a higher and commanding altitude – Point 5455 (“point” refers to the height of hill feature from the mean sea level).

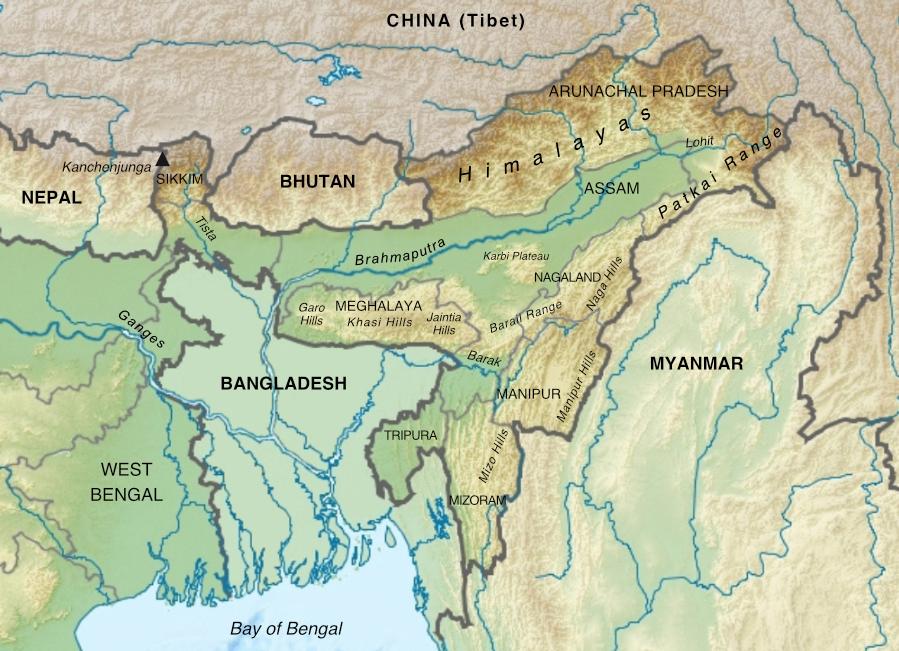

The enemy post dominated Point 5156. Major Duhoon and his men couldn’t afford to be seen in the open, as long as there was light. The only movements possible in the post, were after last light. [Note: All maps have been inserted in the embedded video clip.]

This state of affairs came about because our then-political leadership had rushed into a ceasefire in the 1999 Kargil war before our troops reached the watershed lines. So we didn’t get to occupy the tactically commanding heights which would have made the task easier subsequently for our boys.

The Pakistani post at Point 5455 was 600 metres away from Maj Duhoon’s post, which he manned with 15 soldiers. From the enemy post there was a spur running down towards Point 5156, which the enemy wanted to occupy and hold. That would have made the Indian post tactically untenable.

Red turned the snow

In the first week of February, 2002, at about 1am, the Indian lookouts suspected enemy movement on the spur. Duhoon had already deployed their 7.62mm medium machine gun, with ranges worked out, on a particular spot, covering the spur, as a routine drill. If an enemy patrol reached that point they would opened fire and wipe out the patrol. They were uncertain about the enemy numbers due to heavy mist in the early hours of a dark winter morning.

Bodies fell off the spur and got buried in soft snow. Snowfall started before first light and any tell-tale signs of the enemy soldiers’ remains got obliterated. The Indians were certain of having wiped them out but the numbers were not known to them. The firing at night was reported the next day’s situation report. However, there would be no subsequent situation reporting possible, after the first early morning call in, if the enemy had its way. Simply because there would have been no one left to send in a report thereafter. The Pakistanis were livid and wanted revenge.

Hellfire from the skies

Starting 6am, a punitive barrage of devastating artillery fire was brought down on the Indian post and lasted until last light at 6.30pm. The Pakistanis let loose with all they had. Artillery, rocket-propelled grenades, machine guns, etc.

Normally this kind of sustained barrage with high explosives, from commanding heights within line of sight could even obliterate a small post situated on an exposed hilltop. [Remember what happened to the hapless Pakistani NLI troopers three years back during the Kargil war in that sector?]

Maj Duhoon had organized the post with such eventualities in mind. The 15 men were spread out in single man positions in fox holes or behind boulders, with the command post in a bunker located behind a rock face. This was done to ensure that any possible loss is minimized, even if a shell lands on top the post.

The sole fighting bunker took twenty seven direct hits from enemy RPGs, but it still it stood proudly. [Col Duhoon says it was the worst day which he had experienced during his entire tenure in Batalik.]

Night fell and the barrage stopped. There was not a single Indian casualty. Maj Duhoon had foiled the Pakistani plan to tactically outmanoeuvre his post, wiped out the enemy patrol and kept his men safe, showing the hallmark of brilliance in junior command. [As an interesting conceptual input, please refer to the “CSI Report No. 13, 1989: Tactical Responses to Concentrated Artillery” [pdf] by Combat Studies Institute, US Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. A relevant excerpt given here as a footnote.]

Then in July, they got orders from Army Headquarters for a flag meeting on enemy’s request. The meeting was conducted and the Pakistani side requested Maj Duhoon to allow them to retrieve the bodies of that patrol party. Finally, bodies of five enemy soldiers killed in action were recovered. [Actual visuals of the Pakistanis retrieving the bodies and real time audio of the communication between Maj Duhoon and his Pakistani counterpart are available in the embedded video.]

This is how the macabre score of death came to light. May all fallen fighting men rest in peace, everywhere, while they hold their posts in remote locations, as mandated by their country, wisely or otherwise.

A recent photo of Lieutenant Colonel Anil Duhoon.

A recent photo of Lieutenant Colonel Anil Duhoon.

Video of Lt Col Anil Duhoon telling Sandeep Mukherjee the story in his own words:

Note:

- At 00:51 and 1:26, the year has been mentioned as 2004. It should be 2002.

- At 13:35 and 13:43, Col Duhoon mentions that he stayed in that Batalik post until March 2005. That would be March 2003.

The two errors were inadvertently made and are regretted.

Footnote:

Against an enemy who concentrates significant artillery weapons to neutralize an area of a defender's position, there are three basic defences. The first is to use protection, either by digging in, building field fortifications, or protecting with armour. Protection by engineering reduces mobility and consequently makes forces vulnerable to precision fires. Therefore, engineering activities must be combined with action by some mobile force to avoid the systematic reduction of the overall force over time.

The second method of defence is to thin out one’s forces, as Lossberg did, and to protect those left in place. (German commander in World War I, Oberst Fritz von Lossberg developed what has become the classic concept of elastic defence. This called for a thinning out of forward defences, always subject to destruction by enemy preparation fires). This may make the enemy's task of breaking into a position easier, but forces kept out of the beaten zone are then intact for counterattack and, once intermingled with the attacking enemy, harder to bring indirect fire upon. Lossberg’s response implies a force-oriented defence in which terrain is a tool of defence, not an object. An active counter to neutralization fire is a heavy program of counterfire. The drawback here is that it may be difficult to acquire a clever enemy’s units before they uncover to fire, thus condemning one’s own units to play catch-up, often under fire, a “race” for parity, the most to be expected under these circumstances.

Against precision fires, there are some additional counters. Deception is the most common. If you deny an enemy a target location, precision fire is impossible. A variety of methods have been used successfully: false emitters, dummy positions to draw fire, night occupation, and camouflage discipline. In addition, frequent movement compounds the enemy's problem of targeting in the absence of continuous observation. If you refuse an enemy target identification, he must fall back on area fire and its consequent logistic and temporal burden.

Click here to follow Lt Col Anil Duhoon on Twitter.

Click here to follow Sandeep Mukherjee on Twitter.

Follow us on Twitter here: https://twitter.com/indiasentinels

Follow us on Instagram here: https://instagram.com/indiasentinels

Like our Facebook here: https://facebook.com/indiasentinels