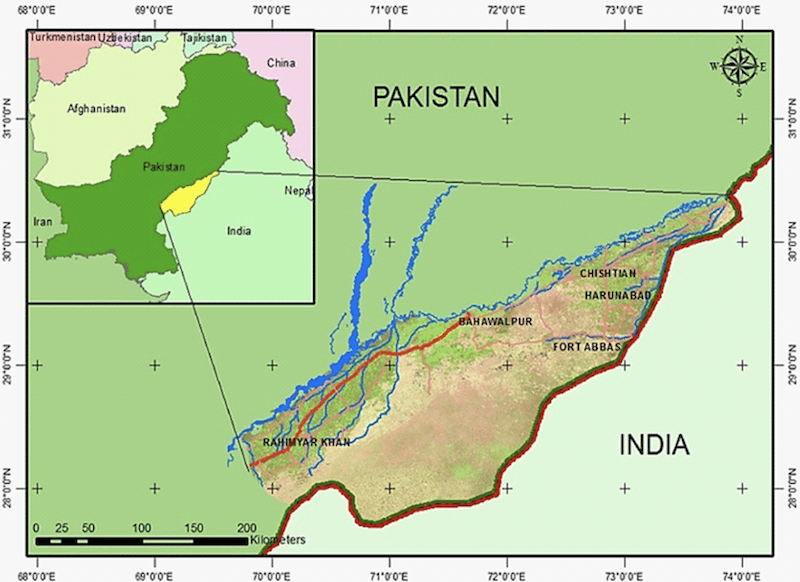

Map of study area showing the extent of the Cholistan desert, major builtup areas of the region, and network of Punjab irrigation main canals. (Image: ResearchGate/Javed Iqbal)

Map of study area showing the extent of the Cholistan desert, major builtup areas of the region, and network of Punjab irrigation main canals. (Image: ResearchGate/Javed Iqbal)

Long before the terrorist attack in Pahalgam and India’s subsequent response to suspend the Indus Waters Treaty, tensions regarding Indus water distribution between the Pakistani provinces of Sindh and Punjab had already been escalating.

The allocation of river water has historically been a contentious matter between the upper riparian province of Punjab and the lower riparian province of Sindh, even before Pakistan’s independence. The origins of this dispute date back to 1901 in undivided India, eventually culminating in the Sindh-Punjab Agreement of 1945.

Following independence, Punjab leveraged its influence within the federal government and its control over governmental resources to secure a larger share of water, much to the dissatisfaction of other provinces, particularly Sindh.

Read also: Pahalgam terror attack is a wake-up call to shed myopic view on J&K proxy war

After Partition, while the Pakistani government negotiated with India to resolve water distribution issues concerning all rivers flowing through both nations, discontent was growing internally regarding the allocation of water among its provinces.

As a water-scarce nation, Pakistan relies heavily on the Indus river, which flows from Tibet to the Arabian Sea, serving as its primary water source and lifeline. In 1960, India and Pakistan signed the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), facilitated by the World Bank, which granted Pakistan 80% of the Indus water, leaving India with a 20% share. The treaty designated the three eastern rivers – Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej – to India, while Pakistan received the majority flow of the three western rivers – Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab.

Interestingly, before the IWT, Dr Saleh Qureshi, a Sindhi who was initially part of the internal negotiations, was removed to suppress any dissenting voice in subsequent water distribution talks. Punjab continued its dominance in water sharing, much to the dismay of other provinces. Subsequently, several committees were established to address the water-sharing conflict, but these efforts proved unsuccessful.

Read also: Will recent Bangladesh-China pact pose new challenge to Siliguri Corridor?

Ultimately, in 1991, a high-powered Indus River System Authority (IRSA) was established to devise a water-sharing agreement. Soon, it became embroiled in controversy in 1994, when Sindh accused Punjab of failing to release water according to the agreed terms. The provincial water dispute remained predominantly unresolved and contentious, despite the implementation of constitutional amendments and the continued operation of the IRSA.

On February 15, 2025, against this backdrop of simmering discontent, the Pakistan Army chief, General Asim Munir, who himself belongs to Punjab, alongside the chief minister of Pakistan’s Punjab, Maryam Nawaz, launched an ambitious Pakistan Army-backed megaproject – the Green Pakistan Initiative. The project entailed converting wasteland into cultivable farmland and modernizing Pakistan’s agriculture to attract foreign and domestic investors for large-scale sustainable development. The development of the Cholistan desert in Punjab was one of the prime objectives of this initiative.

Gen Munir emphasized Punjab’s status as Pakistan’s agricultural hub and commended the province’s leadership and farmers. He assured that the Pakistan Army would provide full support for this developmental initiative.

Read also: How Trump’s tariff plans could reshape US-India defence ties

The initiative, with a budget of $3.3 billion, sought to transform 4.8 million acres of the Cholistan desert, which is adjacent to India, into arable land. The plan included the construction of six canals, drawing water from the Indus and Sutlej rivers. Among these canals, the Cholistan canal, featuring three branches and extending 176 kilometres, was to be of utmost importance. The project served a dual purpose, as it was also to be utilized by the Pakistan Army for military defences.

Quite obviously, this would require an immense quantity of water, diverted upstream, which would predominantly impact Sindh as a downstream region. Sindh expressed its opposition when its representative in the IRSA submitted a dissenting note, voicing concerns that the project could diminish water availability for Sindh province and was being approved without adequate consultation with stakeholders.

Critics of the project argued that the diversion of water would severely impact the lives of Sindh’s residents, who were already facing water shortages. They contended that while the project might foster development for some, it would inevitably lead to deprivation for Sindh.

Read also: Pakistan’s suspension of Shimla pact – Symbolic move with limited impact

The announcement of this project sparked widespread protests across Sindh, which escalated quickly. Despite the proposal receiving approval from Pakistan’s president, Asif Ali Zardari, a native of Sindh, his party, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), did not hesitate to protest against the project. His son, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, led the demonstrations, demanding an immediate halt to the canal project and threatening to withdraw support from the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) party led by the country’s prime minister, Shehbaz Sharif. The people of Sindh took to the streets, and the road to Punjab was blocked in protest.

While these protests were ongoing in Sindh, a terrorist attack took place in Pahalgam, India, on April 22, 2025, prompting the Indian government on April 23 to hold Pakistan accountable and suspend the Indus Waters Treaty as an initial response. This shocked Pakistan, which had always considered the IWT as inviolable due to the mediation of the World Bank. This new development further complicated the prospects of the ambitious canals project, already facing resistance due to the water dispute between Sindh and Punjab.

Read also: IWT suspension – A symbolic move with long-term implications

Experts noted that while India may not have the full capacity to divert its entire share of Indus water immediately, it could still manage to limit or control water flow to some degree, potentially diminishing Pakistan’s water supply and creating challenges for the country.

India, on the other hand, appeared resolute to restrict water flow to Pakistan. It outlined short-term, medium-term, and long-term strategies to ensure minimal water reaches Pakistan, with river desilting being a key immediate focus of the short-term plan. Desilting is significant as it enhances river capacity and can help redirect water flow away from international borders.

It is noteworthy that the protests in Sindh had been ongoing for months before the Pahalgam terrorist incident, but Pakistan’s PML-N-led government was confident that a consensus on this issue with the leaders of Sindh was only a matter of time until the Pakistan Army decided to get involved. Since no political party in Pakistan could effectively oppose the wishes of the Army, this project – practically owned by the military – was virtually unstoppable.

But what upset the calculus was India’s unprecedented decision to suspend the IWT. This added a new dimension of uncertainty, previously unfactored, to this high-value investment. While designing the project, Pakistan had relied on the IWT’s integrity, as it was facilitated by the World Bank. Yet, with a single announcement, India distanced itself from any assured water flow stipulated in the agreement.

This potential water shortfall from India not only jeopardized the project’s viability but also signalled who would truly control its direction. Pakistan soon recognized that it risked compromising the strategic independence of this national asset.

On April 25, Shehbaz Sharif, accompanied by Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, announced the project’s suspension, possibly on instructions from the Pakistan Army. Although this suspension was described as temporary, the chances of the project’s reinstatement and Gen Munir’s dream of seeing Cholistan green seem minimal until India relents.

He, on his part, must remain cognizant of India’s stance on the IWT: “Blood and water cannot flow together.”

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect the views of India Sentinels.

Follow us on social media for quick updates, new photos, videos, and more.

X: https://x.com/indiasentinels

Facebook: https://facebook.com/indiasentinels

Instagram: https://instagram.com/indiasentinels

YouTube: https://youtube.com/indiasentinels

© India Sentinels 2025-26