Map showing Damak, Nepal; Siliguri Corridor (marked by two thin red lines); Lalmonirhat, Bangladesh; and Gelephu, Bhutan. Also shown is the 2017 India-China standoff site at Doklam. (Google Maps)

Map showing Damak, Nepal; Siliguri Corridor (marked by two thin red lines); Lalmonirhat, Bangladesh; and Gelephu, Bhutan. Also shown is the 2017 India-China standoff site at Doklam. (Google Maps)

Pakistan’s military spokesman, Lieutenant General Ahmed Sharif Chaudhry, recently declared, while talking to a western media outlet, that Islamabad would strike “deeper within India” and “start from the east” in any future conflict. This wasn’t mere sabre-rattling. When viewed alongside the informal trilateral meeting between Bangladesh, China, and Pakistan in Kunming this past June – ostensibly focused on “deeper cooperation” but unmistakably strategic in timing and composition – a disturbing pattern emerges: the materialization of a coordinated threat matrix designed to exploit India’s most vulnerable geographical bottleneck.

Having stood guard and commanded troops across every section of the line of actual control (LAC) from Arunachal Pradesh to Ladakh, this author has witnessed firsthand how our adversaries study our vulnerabilities with meticulous patience. That patience now appears to be yielding a sophisticated strategy of encirclement that threatens to transform India’s northeastern lifeline into a noose around our national security.

The Spectre of Strategic Encirclement

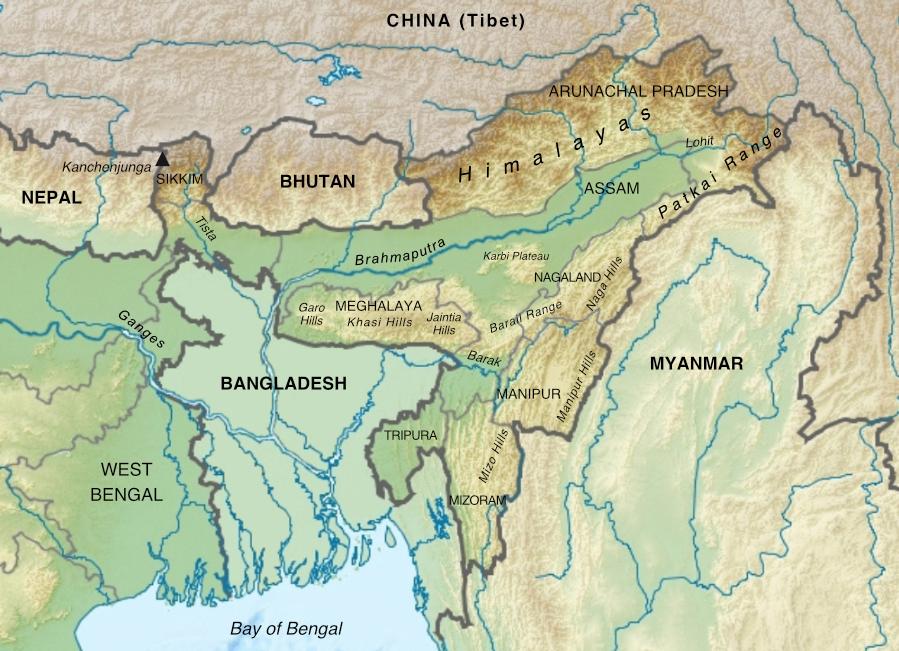

The spectre of strategic encirclement around India’s Siliguri Corridor has long haunted military planners and security analysts. Today, three nodes – Damak in Nepal, Lalmonirhat in Bangladesh, and Gelephu in Bhutan – have begun forming what strategic circles now term the “Devil’s Triangle.”

These points, positioned around the Siliguri Corridor, which is also called “Chicken’s Neck”, enable China to orchestrate a multifaceted threat against India’s most fragile lifeline to its northeastern states. This triangle represents a multi-domain, multi-front threat that embodies the lived reality of India’s evolving security landscape.

This corridor, sometimes as narrow as 20 kilometres – narrower than the distance between Delhi’s Connaught Place and Uttam Nagar – is the only overland link between mainland India and the northeast. Its loss, even temporarily, would cut off 45 million Indians and unravel India’s territorial integrity in the east. The Devil’s Triangle is not merely geographical – it represents a convergence of infrastructural, economic, and political pressures that could be activated in coordinated fashion.

Read also: China’s Brahmaputra Gambit – A strategic assessment of Motuo dam

The Three Nodes of Peril

Damak, Nepal: It sits 55 kilometres from the Indian border and just 77 kilometres west from the Siliguri town itself. Damak is now hosting China’s Belt and Road Initiative through the China-Nepal Friendship Industrial Park. Masquerading as civilian development, this facility can rapidly transform into a military platform. Recent satellite imagery reveals road networks designed to facilitate quick military movements, with Chinese personnel conducting surveys well beyond the park’s official boundaries.

Lalmonirhat, Bangladesh: It houses a former World War II airfield that could be modernized for dual-use purposes with Chinese assistance. At just 12–20 kilometres from the India border and under 175 kilometres by road from Siliguri town, its activation would dramatically expand threat vectors. Intelligence reports suggest Chinese feasibility studies for runway extensions and radar installations under civil aviation pretexts.

Bangladesh’s increasing economic dependence on China – bilateral trade exceeding $25 billion and arms purchases making it Beijing’s second-largest weapons buyer in South Asia – creates political leverage that directly threatens Indian interests.

Gelephu, Bhutan: This Bhutanese town is right on the border with India’s Assam and 48 kilometres by road to the strategic town of Bongaigaon and less than 100 kilometres from the Chicken’s Neck. It hosts the ambitious “Mindfulness City” project – a trillion-rupee development with significant Chinese investment interest. This represents a departure from Bhutan’s historically cautious foreign policy, creating potential dual-use applications that compromise India’s security arrangements with its traditionally closest regional ally.

China’s Comprehensive Strategy

China’s challenge through the Devil’s Triangle encompasses multiple dimensions of modern hybrid warfare. The approach combines traditional military pressure with sophisticated political and economic manipulation.

Beijing’s salami-slicing continues along the LAC, with incremental encroachments tested and refined over decades. The Galwan valley incident of June 2020, where 20 Indian soldiers lost their lives in the deadliest border clash in 45 years, exemplified this strategy of creating new ground realities while avoiding full-scale conflict.

Its dual-use infrastructure development proceeds at unprecedented pace. Roads, airfields, and industrial parks officially designated for civilian purposes are optimized for People’s Liberation Army movement and rapid crisis mobilization. China’s template, proven from the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor to the Hambantota port, is being replicated across India’s periphery.

For years now, we have seen China’s economic leverage through debt-trap diplomacy establishes dependencies that translate into political pressure. Nepal’s growing reliance on Chinese investment, Bangladesh’s arms purchases, and Bhutan’s opening to foreign investment all reflect Beijing’s patient strategy of building influence through economic integration.

Read also: Network-Centric Warfare – Pakistan’s edge and India’s wake-up call

Neighbourhood Volatility

For India, Bangladesh presents the most immediate concern in the region. Political turbulence, an interim government, and mounting economic pressures have created conditions ripe for anti-India sentiment. Hostile rhetoric from opportunistic politicians using India as a domestic scapegoat reflects deeper structural changes where traditional pro-India sentiment faces challenge from newer political forces.

The potential for Bangladesh’s military or intelligence elements to allow hostile use of territory cannot be dismissed. Complex civil-military dynamics create opportunities for unofficial cooperation with external powers, particularly concerning given facilities like Lalmonirhat’s dual-use potential.

Nepal’s political pendulum swings between socialist-republican, monarchist, and centrist coalitions, producing erratic foreign relations. The 2020 cartographic crisis, when Kathmandu released maps claiming Indian territory including Kalapani and Lipulekh, demonstrated willingness to use anti-India posturing for domestic gain. The timing during the Galwan crisis suggested coordination with broader regional dynamics.

Nepal’s enthusiasm for Chinese projects, including the proposed trans-Himalayan railway, offers alternatives to traditional Indian dependence while providing China unprecedented strategic access.

As far as Bhutan is concerned, it has been traditionally India’s most reliable partner. However, has been showing subtle but significant changes. The Mindfulness City project, foreign investment policy amendments, and behind-the-scenes border negotiations with China signal recalibration on Thimpu’s part. Any border agreement between Bhutan and China would fundamentally impact India’s regional security arrangements.

The Multi-Directional Threat Matrix

The Devil’s Triangle’s danger lies in potential coordinated, multi-directional pressure overwhelming India’s traditional response mechanisms. Indian military doctrine, historically focused on sectoral responses – north for China, west for Pakistan – faces fundamental challenge from simultaneous threats across multiple vectors.

Northern approaches through the Chumbi valley provide the PLA direct access to threaten the corridor through rapid operations. Eastern threats emerge from Bangladesh’s potential role in electronic surveillance and subversive activities. Western pressure develops through Nepal’s transformation into a logistics node with coordinated disruption capabilities.

Every triangle node maintains plausible civilian cover, making traditional military responses inappropriate. Airstrips for cargo can accommodate military aircraft; industrial parks can stockpile military equipment; communication networks provide intelligence penetration deep into Indian territory.

Political manipulation ensures each crisis in Nepal and Bangladesh provides China opportunities to expand influence while constraining India’s options. This hybrid warfare strategy pursues military objectives through political means while maintaining plausible deniability.

Read also: With FM Munir in Pakistan’s charge, India must see the ‘black swan’ coming

Threat Activation Scenarios

Crisis activation would likely begin with Chinese pressure elsewhere along the LAC, forcing India to mobilize integrated battle groups away from corridor security. Simultaneous civilian unrest in West Bengal or Assam, potentially supported across borders, would trigger internal security deployments, further stretching resources.

Direct action might involve railway sabotage disguised as accidents, sudden border closures justified by internal security, or airspace violations under various pretexts. Bhutan’s traditional openness might be restricted through administrative complications over the Mindfulness City project.

The combination of diplomatic protests, civilian blockades, and limited kinetic actions could render the Chicken’s Neck unusable for extended periods, forcing India to rely entirely on airlift capabilities while facing potential northeastern isolation.

India’s Achievements and Gaps

India has initiated infrastructure upgrades and regular joint-services military exercises in the region, which demonstrated threat awareness. However, significant gaps remain. The Kaladan Multimodal Transit project through Myanmar faces delays and security challenges limiting its utility as corridor backup. Airlift capacity, while substantial, cannot sustain 45 million people indefinitely.

Diplomatically, India’s traditional soft power approach has not matched China’s transactional assistance model. Beijing’s immediate, visible benefits without governance conditionalities prove attractive to leaders facing domestic pressures. India’s failure to anticipate political transitions repeatedly places New Delhi at disadvantage during relationship-forming periods.

Chinese technical platforms increasingly monitor Indian communications through civilian assets across all three countries, creating persistent vulnerabilities traditional military responses cannot address. Our counterintelligence resources remain insufficient for monitoring all potentially hostile development projects.

Read also: India mustn’t take Pakistan COAS’s promotion to field marshal lightly

Strategic Imperatives

Addressing the Devil’s Triangle requires comprehensive transformation combining military preparation with diplomatic innovation and economic strategy.

India’s strategic depth development must prioritize high-speed, all-weather alternative corridors through Brahmaputra river systems and enhanced air bridges as essential national security infrastructure. Underground or hardened logistics networks in corridor bottlenecks, designed to withstand aerial attack, provide necessary resilience.

Our regional security architecture demands a Siliguri Corridor “security compact” involving trilateral cooperation focused on corridor resilience, including rapid information sharing and coordinated greyzone responses. A counter-BRI coalition offering transparent development alternatives could provide genuine choices while securing corridor interests.

India’s intelligence enhancement requires dedicated monitoring of dual-use projects within 100 kilometres of the corridor, staffed by military-technical specialists. Targeted influence operations must highlight debt-trap risks while showcasing transparent Indian connectivity benefits.

Also, our military doctrine must accommodate prepositioned air-mobile units trained for corridor recovery, equipped for simultaneous internal and external threats. Regular war-gaming must test the integration between the armed forces and the paramilitary forces/central armed police forces during complex scenarios combining conventional threats with internal security challenges.

Apart from the above, enhanced diplomacy through Track II exchanges can provide early warning while building relationships transcending political changes. Economic cooperation must explicitly link market access with corridor-security adherence, clearly communicated and consistently enforced.

Read also: Beijing cannot dictate the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation

The Imperative for Action

The Devil’s Triangle embodies a fundamental threat to India’s territorial integrity. China’s patient infrastructure strategy shows no signs of slowing, while Bangladesh’s instability and Nepal’s oscillating loyalties create permanent vulnerabilities. Bhutan’s opening to foreign investment could fundamentally alter regional strategic balance.

The Siliguri Corridor must never become a modern choke point determining national fate. Its vulnerability threatens not only military logistics but economic, political, and social connections binding northeastern states to the national mainstream.

India’s response must match the threat’s sophistication, combining traditional military preparation with innovative approaches to economic competition and political influence. The time for incremental responses has passed. Success requires sustained commitment across electoral cycles, professional execution across government departments, and public understanding of stakes involved.

The northeastern states represent more than territory – they embody India’s diversity, natural resources, and strategic depth. To lose the Chicken’s Neck would risk losing national cohesion in the east.

Read also: Threat of China annexing Tawang is real. What must India do?

The Gathering Storm

Lt Gen Chaudhry’s declaration that Pakistan would “start from the east”, coupled with the Kunming trilateral meeting between Dhaka, Beijing, and Islamabad, removes any remaining ambiguity about our adversaries’ intentions. The informal nature of the meeting – ostensibly focused on infrastructure and trade – mirrors China’s preferred strategy of advancing objectives through seemingly benign multilateral cooperation. When Pakistan’s eastern strategy aligns with Bangladesh’s post-Hasina pivot toward China, the result is a three-dimensional threat demanding immediate and comprehensive response.

As a soldier who has defended India’s borders for decades, this author recognizes that wars are rarely won by those who prepare for the last conflict. The Devil’s Triangle represents tomorrow’s battlefield – a domain where traditional military responses prove inadequate against hybrid threats that blur the lines between peace and war, civilian and military, economic cooperation and strategic coercion.

The window for effective action remains open, but it narrows with each passing month. India must respond with the urgency this triangle of threats demands, lest we discover too late that our most vital corridor has become our greatest vulnerability. The stakes could not be higher: the territorial integrity of our nation and the security of 45 million fellow Indians depend upon our strategic wisdom and political will in the months ahead.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect the views of India Sentinels.

Follow us on social media for quick updates, new photos, videos, and more.

X: https://twitter.com/indiasentinels

Facebook: https://facebook.com/indiasentinels

Instagram: https://instagram.com/indiasentinels

YouTube: https://youtube.com/indiasentinels

© India Sentinels 2025-26