Yarlung Tsangpo river’s “Great Bend” in China’s Tibet Autonomous Region, close to India’s Arunachal Pradesh, where the megadam will be built. (Photo courtesy: China News Service)

Yarlung Tsangpo river’s “Great Bend” in China’s Tibet Autonomous Region, close to India’s Arunachal Pradesh, where the megadam will be built. (Photo courtesy: China News Service)

China’s audacious decision to construct the world’s largest hydropower project on the Yarlung Tsangpo – just upstream from where it enters India as the Brahmaputra – represents far more than an engineering marvel. It is a calculated geopolitical manoeuvre that fundamentally alters the strategic landscape of South Asia.

As a veteran military officer who had commanded troops on all sectors along the line of actual control (LAC) with China, this author has witnessed firsthand how geography shapes strategy. The announcement of the Motuo Hydropower Station, also called Medog Hydropower Station, with its staggering 60-gigawatt capacity and $167 billion price tag, is China’s latest assertion of dominance over the Himalayan watershed. This is not merely about electricity generation; it is about power in its most elemental form – control over the lifeblood of nations.

The Strategic Choke Point

The new dam will be so gigantic that it will dwarf the Three Gorges Dam, which spans the Yangtze river near Sandouping in Yichang, Hubei province. For perspective, the Three Gorges Dam slows Earth’s rotation by adding 0.06 microseconds to the length of a day, which is significant for a man-made structure but negligible for life on the planet.

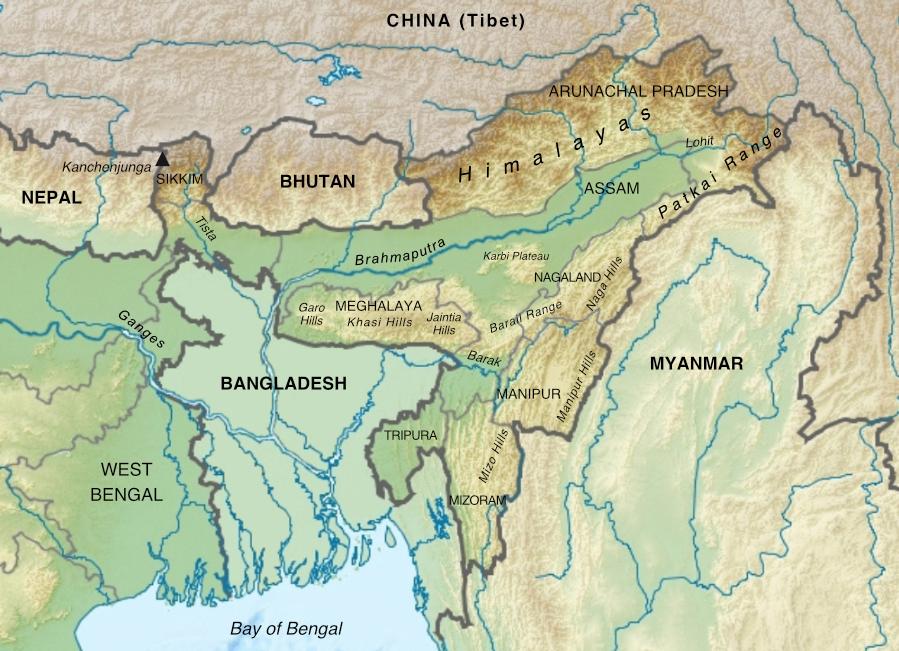

Now, the upcoming dam’s location at the “Great Bend” – where the Yarlung Tsangpo executes a dramatic U-turn before entering Arunachal Pradesh – is no coincidence. This geological feature represents one of the most strategically significant points in Asia’s hydrological architecture. Here, the river’s flow surges from 31.2 billion cubic metres annually to approximately 135.9 billion cubic metres, making it the perfect chokepoint for upstream control.

Beijing’s protestations that this is merely a “run-of-the-river project” ring hollow when confronted with the dam’s unprecedented scale. No structure of this magnitude can claim to have minimal impact on flow patterns. The very physics of such an undertaking ensures significant manipulation capabilities, whether intended or not.

From a military strategist’s perspective, the dam creates what we might term “hydrostrategic leverage” – the ability to influence downstream behaviour through water control. This represents a new dimension in China’s comprehensive national power projection, complementing its military and economic instruments.

What makes this particularly concerning is China’s existing portfolio of upstream dams. The Zangmu, Gyatsa, and Jiacha dams already operational on the Yarlung Tsangpo, combined with the planned Dagu and Daduqia projects, create a cascade system that amplifies Beijing’s control. The Motuo dam represents not an isolated project but the crown jewel in a comprehensive upstream infrastructure network.

Read also: Network-Centric Warfare – Pakistan’s edge and India’s wake-up call

The Weapon of Water

The spectre of “water weaponization” is not mere alarmism; it is a legitimate strategic concern that demands serious consideration. China now possesses the theoretical capability to induce artificial floods during monsoon seasons or exacerbate droughts during lean periods. Such actions would not require overt military aggression yet could achieve strategic objectives through environmental manipulation.

Consider the implications during a border standoff. China could, without firing a shot, create humanitarian crises in Assam or Arunachal Pradesh through strategic water releases. Conversely, withholding water during critical agricultural seasons could pressure India’s negotiating position. This is asymmetric warfare adapted for the 21st century.

The catastrophic dam-failure scenario, while extreme, cannot be dismissed entirely. Whether through natural disaster, sabotage, or conflict, the collapse of such a massive structure would unleash unprecedented destruction across northeastern India. Our disaster preparedness mechanisms, already strained by annual flooding, would be utterly overwhelmed by such an eventuality.

Recent seismic activity in the region adds another dimension to this concern. The 2017 Mainling earthquake in Tibet, measuring 6.9 on the Richter scale, occurred merely 30 kilometres from several existing dams. The Yarlung Tsangpo basin sits atop active fault lines, making seismic risks a genuine consideration for such massive infrastructure.

India’s Vulnerability and Response

Our vulnerability stems not merely from downstream positioning but from decades of inadequate infrastructure development for water management, including storage, diversion, utilization, etc. While China has been systematically damming the Tibetan plateau, India has lagged in creating strategic water-storage capabilities in the northeast.

This infrastructure deficit becomes starkly apparent when comparing national approaches. China’s 14th Five-Year Plan allocates substantial resources to Tibetan hydropower development, treating it as both energy security and strategic leverage. India’s northeastern hydel projects, by contrast, have faced persistent delays due to environmental clearances, local resistance, and inadequate investment.

The timing of China’s announcement is also telling. Coming amid heightened border tensions and India’s infrastructure push in Arunachal Pradesh, the dam serves multiple strategic purposes. It signals Chinese resolve in disputed territories while creating new pressure points in bilateral relations.

Read also: Beijing cannot dictate the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation

The ecological implications extend beyond immediate water availability. The Brahmaputra’s sediment transport – crucial for maintaining soil fertility and delta formation – faces significant alteration. Although much of the river’s sediment load originates from Indian catchments rather than Tibet, any upstream disruption creates cascading effects downstream.

The impact on Kaziranga National Park and similar ecosystems could be profound. Altered flow patterns threaten migratory species, fishing communities, and the delicate balance that has sustained millions of livelihoods for generations.

The Data Opacity Problem

Perhaps most troubling is China’s historical opacity regarding hydrological data sharing. Existing memoranda of understanding provide limited flood-season information, but comprehensive, real-time data remains elusive. This information asymmetry compounds India’s strategic disadvantage and hampers effective disaster preparedness.

The 2017 Doklam standoff demonstrated how water disputes can escalate rapidly. During that crisis, China briefly suspended hydrological data sharing – a reminder of how quickly technical cooperation can become a casualty of political tensions. More recently, China’s delayed flood warnings in 2020 contributed to devastating floods in Assam, highlighting the practical consequences of information gaps.

Military doctrine emphasizes the importance of intelligence in countering threats. In hydro-strategic terms, reliable water-flow data represents critical intelligence. China’s reluctance to provide comprehensive information suggests awareness of the strategic value of this data asymmetry.

India’s Strategic Options

Our response must be multifaceted and urgent. First, accelerating construction of the Upper Siang multipurpose project and similar storage facilities is essential. These structures serve dual purposes: providing water security and creating strategic buffers against unpredictable upstream releases.

Second, we must invest heavily in advanced flood forecasting and early warning systems. Technology can partially compensate for our geographical disadvantage by providing crucial response time during emergency scenarios.

Read also: With FM Munir in Pakistan’s charge, India must see the ‘black swan’ coming

Third, diplomatic engagement remains vital despite its limitations. Pushing for binding international agreements on transboundary river management, while challenging given China’s position, represents our best hope for institutionalized cooperation.

Fourth, enhancing regional cooperation with Bangladesh and other downstream nations could dilute the bilateral power imbalance. A multilateral approach may prove more effective than purely bilateral negotiations. Bangladesh, which receives nearly 54% of the Brahmaputra’s annual flow, shares our concerns about upstream manipulation and could become a valuable partner in multilateral forums.

Fifth, India must accelerate its space-based monitoring capabilities. Our recent advances in satellite technology, including the RISAT constellation, provide opportunities for independent hydrological monitoring that reduces dependence on Chinese data sharing. Real-time satellite observation of reservoir levels and flow patterns could provide crucial early warning capabilities.

The Broader Himalayan Contest

This dam must be understood within the broader context of China’s Himalayan strategy. Beijing is systematically altering the region’s hydrological landscape through multiple projects, creating what some analysts term a “water tower” under Chinese control. (Tibet is also called the Water Tower of Asia.)

The location near disputed Arunachal Pradesh adds another layer of complexity. Water disputes could easily become entangled with territorial disagreements, creating multiple pressure points in an already volatile relationship.

China’s dam construction also intersects with its broader Belt and Road Initiative. Beijing has offered similar hydropower projects to neighbouring countries – including Pakistan’s Diamer-Bhasha dam – as part of its connectivity agenda. This creates a template for infrastructure-based influence that extends well beyond bilateral China-India relations.

Read also: India mustn’t take Pakistan COAS’s promotion to field marshal lightly

Realism Over Alarmism

However, we must remember that while the threat is real, we must avoid both complacency and panic. The Brahmaputra’s massive monsoon-fed flow and multiple Indian tributaries mean China cannot simply “turn off the tap” and create permanent water scarcity. The river’s annual discharge grows from approximately 136 billion cubic metres at the dam site to over 600 billion cubic metres by the time it reaches Bangladesh, primarily due to Indian rainfall and tributary contributions.

Nonetheless, temporary disruptions during dam filling, maintenance, or strategic manipulation could create significant localized impacts. The threat is not existential, but it is serious enough to warrant comprehensive contingency planning.

India’s own experience with interstate water disputes – from Cauvery to Ravi-Beas – demonstrates how quickly technical disagreements can escalate into political crises. The added complexity of international boundaries and strategic competition magnifies these risks exponentially.

The Path Forward

India’s response must combine strategic patience with tactical urgency. We cannot prevent China’s dam construction, but we can mitigate its potential impacts through robust preparation and adaptive management.

Investment in water-storage infrastructure, flood-management systems, and regional cooperation represents our best defence against hydro-strategic vulnerability. Simultaneously, we must continue pressing for transparency and data sharing while preparing for scenarios where such cooperation remains limited.

The Motuo dam represents a new chapter in India-China strategic competition. China has gained a powerful new instrument of influence, but India retains significant cards to play. How we choose to play them will determine whether this engineering marvel becomes a source of regional cooperation or strategic coercion.

Read also: Threat of China annexing Tawang is real. What must India do?

The stakes could not be higher. The Brahmaputra is not merely a river; it is the lifeline of northeastern India and eastern Bangladesh. Securing its future requires the same strategic commitment we would dedicate to defending any vital national asset.

China’s Brahmaputra gambit challenges India to think strategically about water security in ways we have long avoided. The question is not whether we can stop this dam – we cannot. The question is whether we can adapt swiftly enough to maintain our strategic autonomy in a world where water has become a weapon of statecraft.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect the views of India Sentinels.

Follow us on social media for quick updates, new photos, videos, and more.

X: https://twitter.com/indiasentinels

Facebook: https://facebook.com/indiasentinels

Instagram: https://instagram.com/indiasentinels

YouTube: https://youtube.com/indiasentinels

© India Sentinels 2025-26