Illustration for representation. (© India Sentinels 2026–27)

Illustration for representation. (© India Sentinels 2026–27)

New Delhi: The United States supreme court delivered one of the most consequential trade-law judgments in a generation, on Friday. In a 6–3 ruling, the court held that the president, Donald Trump, had exceeded his authority by invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) – a 1977 statute designed for targeted economic sanctions in genuine crises – to impose sweeping, universal import tariffs. The US supreme court head, Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, held that the power to “regulate importation” under IEEPA did not confer the power to redesign the nation’s entire tariff schedule.

The ruling annulled a large share of the emergency-based levies, exposed the administration to potentially tens of billions of dollars in refund claims, and significantly narrowed future use of national-emergency authority for trade policy.

Trump’s reaction was volcanic. On Truth Social, his own social media platform, he called the majority justices – including some he had himself appointed – “fools”, “lapdogs”, and “disgraceful”, and branded the ruling “ridiculously” and “extraordinarily anti-American”. At a White House media interaction, he warned that importers should not expect smooth refunds on the more than $100 billion in duties collected under the now-voided orders and signalled prolonged litigation. Yet even as he raged, his administration was already working on what came next.

The dissent, authored by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, was more useful to the White House than Trump’s public statements let on. Kavanaugh argued that the court had curtailed only IEEPA-based tariffs, leaving intact other statutory pathways through which a president could impose duties. Within hours of the verdict, the administration was already exploiting precisely that gap.

Dormant Clause Awakened

Rather than accept defeat, Trump immediately announced a fresh 10% “worldwide tariff” on nearly all imported goods, framing it as a legally clean replacement for the struck-down levies. This time the legal hook was Section 122 of the country’s Trade Act of 1974 – a little-used provision that authorizes a president to impose across-the-board tariffs of up to 15% for up to 150 days to address a “large and serious” US balance-of-payments deficit.

According to a White House fact sheet, the 10% duty was to take effect from February 24, 2026, at 12.01am Washington time.

Section 122 had been considered a largely dormant clause. No previous president had ever deployed it on this scale or in this non-country-specific, global manner. Its 150-day ceiling and the requirement for congressional approval to extend it were precisely the features that made earlier administrations wary of it. But for an administration intent on maintaining tariff pressure after a judicial rebuff, its very existence was enough.

On Saturday, barely 24 hours after the 10% announcement, Trump escalated again. He declared via Truth Social that he would raise the global surcharge “to the fully allowed, and legally tested, 15% level”, effective immediately. Multiple international media outlets confirmed the White House intended to use the same Section 122 authority for this second escalation.

Legal experts remain divided on whether the statute can sustain such aggressive use; it is on the books but applying it as a permanent-seeming instrument across all trading partners is without precedent. Fresh legal challenges are expected. For now, unless courts intervene or Congress refuses to renew the measure after 150 days, the 15% surcharge is the operative reality for every trading partner – India included.

India’s Tariff Position

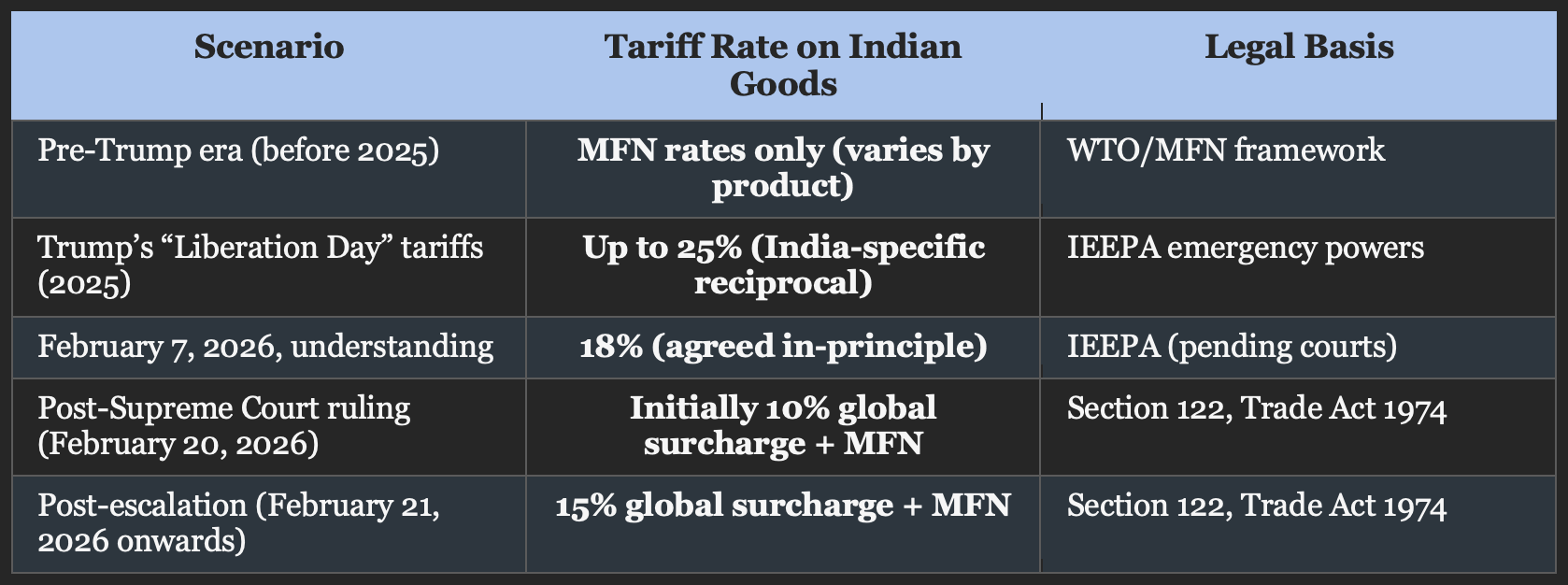

India had been among the harder-hit targets of Trump’s tariff activism. The “Liberation Day” levy regime, announced in 2025 and grounded in IEEPA, had imposed duties of up to 50% – 25% on Indian goods, citing India’s own applied tariffs and an additional 25% for its continued purchase of discounted Russian oil. An in-principle understanding, reached on February 7 envisaged a reduced – but still elevated – rate of 18% in exchange for Indian policy concessions. The US apex court’s ruling has erased the legal basis for all of that.

In its place, India now faces the same 15% global surcharge as virtually every other US trading partner, applied on top of the standard “most favoured nation” (MFN) product-specific duties that the US has always charged. The net effect is paradoxical. Relative to the threatened 25% or the agreed 18% reciprocal rate, the new 15% ceiling is less punitive. Relative to the pre-Trump era, when Indian exports faced only MFN rates, it still represents a significant additional burden – and one with an uncertain shelf life.

India’s goods exports to the US reached approximately $86.5 billion in FY 2024–25, making the US India’s single largest merchandise export destination. The new tariff architecture will compress margins across every category.

How the Tariff on Indian Goods Has Shifted Source: Compiled from White House fact sheets and Reuters.

Source: Compiled from White House fact sheets and Reuters.

Sector by Sector: Where the Pressure Lands

Pharmaceuticals are India’s most strategically significant – and, in this context, potentially most insulated – export category. Indian generic manufacturers supply a substantial share of the US generic medicine market. Their demand is relatively inelastic, meaning US distributors and insurers will absorb part of the tariff increase rather than allow shortages.

Over time, however, even thin-margin generic producers may face pressure to cut prices, shift packaging operations to the US, or route exports via third countries with lower tariff exposure. The Trump administration has signalled possible carve-outs for pharmaceuticals, given the domestic political sensitivity of drug pricing in the US – a factor that Indian negotiators should exploit actively.

Gems and jewellery – India’s second-largest goods export category to the US – is far more exposed. The sector is price-sensitive, and a 15% surcharge risks eroding India’s competitiveness against rivals in Southeast Asia and Latin America, especially in mid-market jewellery where brand loyalty is weaker. India’s dominance in diamond cutting and polishing gives it some structural advantage, but that may not be sufficient if buyers shift sourcing to avoid the additional cost.

Engineering goods, electrical machinery and mechanical appliances sit in a more complex position. These exports are integrated into US value chains, and reshoring or re-sourcing takes time. Crucially, if all major suppliers – China, Vietnam, Mexico and India – face the same 15% blanket duty, India’s relative competitiveness does not necessarily worsen. The risk is that the total market shrinks as US manufacturers turn to domestic suppliers, or that the 150-day time limit on Section 122 tariffs introduces enough uncertainty that US buyers defer large orders entirely.

Textiles and apparel present a different challenge. India competes here against Bangladesh and Vietnam, both of which face the same new tariff floor. Relative competitiveness will depend on cost compression and product mix. For smaller Indian exporters, the administrative burden of managing potential refund claims should the tariffs eventually be struck down – a real legal possibility – could itself prove disruptive.

Iron, steel and other industrial inputs face cumulative pressure, having already absorbed waves of Trump-era protection under earlier statutes.

Services: The Insulated Core

A substantial share of India’s economic relationship with the US is conducted in services – IT, business process outsourcing, consulting and professional services – none of which are touched by the Section 122 tariff, which formally applies only to goods. India’s IT and business services exports to the US, which generate high-value jobs and significant foreign exchange, are structurally insulated from this specific battle. In 2024, telecommunications, computer and IT services alone accounted for over 40% of US services imports from India. That cushion matters enormously when assessing the overall bilateral economic relationship.

The indirect risks, however, cannot be ignored. Sustained tariff uncertainty, slower US economic growth, or a broader chilling of corporate sentiment towards global sourcing could, over time, affect demand for Indian services. The strategic logic of deepening services-led engagement – where tariffs are not the main policy lever – is therefore as compelling as ever.

New Delhi’s Response

India’s official reaction has been measured, deliberately so. The commerce ministry said it had “noted” the US supreme court judgment and that “some steps” had been announced by the administration, adding that it was “studying all these developments for their implications.” This language is textbook New Delhi – acknowledge, avoid public escalation, and preserve room to manoeuvre in private channels.

The Federation of Indian Export Organizations struck a cautiously optimistic note, arguing that a flat global tariff of 15% is still preferable to a higher, India-specific reciprocal rate.

Reuters reported on Sunday that India had quietly delayed a planned round of high-level trade talks with the US following Trump’s escalation to 15%. The postponement – confirmed as a decision taken after consultations between officials in both capitals – was one of the first concrete policy responses in Asia to the post-verdict tariff shake-up. It signals that New Delhi neither wants a public rupture nor intends to pretend that nothing has changed.

Within India’s policy community, several priorities are now in play: assessing product-wise exposure to the 15% duty; identifying sectors – particularly pharmaceuticals and critical minerals – where India can make a credible case for exemptions on grounds of US strategic interest; and exploring coordination with other affected economies in G20 and WTO forums. The prime minister, Narendra Modi, who has invested personal political capital in framing India–US ties as a cornerstone of India’s growth strategy, will need to balance industry concerns with the imperative of keeping the broader partnership on track.

Three Variables India Can’t Afford to Ignore

The first is the legal fate of Section 122 in its current form. The statute is real, but its use at this global scale is unprecedented. Legal challenges are expected, and if courts strike down this round of tariffs too, or if Congress declines to renew them after 150 days, the US tariff regime could go through yet another convulsion – with Indian exporters caught in the middle of each cycle.

The second is US domestic politics. Trump has made tariffs a central part of his political identity and his case to working-class voters. Congressional representatives from import-dependent states and business lobbies opposed to higher costs could become a moderating force. How that internal tension resolves will determine whether the 15% rate is extended, modified or quietly allowed to expire.

The third is India’s own strategic agency. The US supreme court’s ruling, paradoxically, has improved India’s negotiating position by removing the legal basis for the most punitive, India-specific surcharges. New Delhi can now press for product-specific relief in sectors of clear US strategic interest, accelerate diversification of its export markets to reduce vulnerability to American policy swings, and push the conversation towards digital trade and services – areas where the tariff instrument is far less relevant.

The broader lesson from this episode is as important as any specific tariff rate. Even the world’s most powerful executive faces institutional checks. India’s task is to navigate the volatility of American domestic politics without losing sight of the long-term logic – and opportunity – of a closer economic and strategic partnership with the United States.

Follow us on social media for quick updates, new photos, videos, and more.

X: https://twitter.com/indiasentinels

Facebook: https://facebook.com/indiasentinels

Instagram: https://instagram.com/indiasentinels

YouTube: https://youtube.com/indiasentinels

© India Sentinels 2025-26