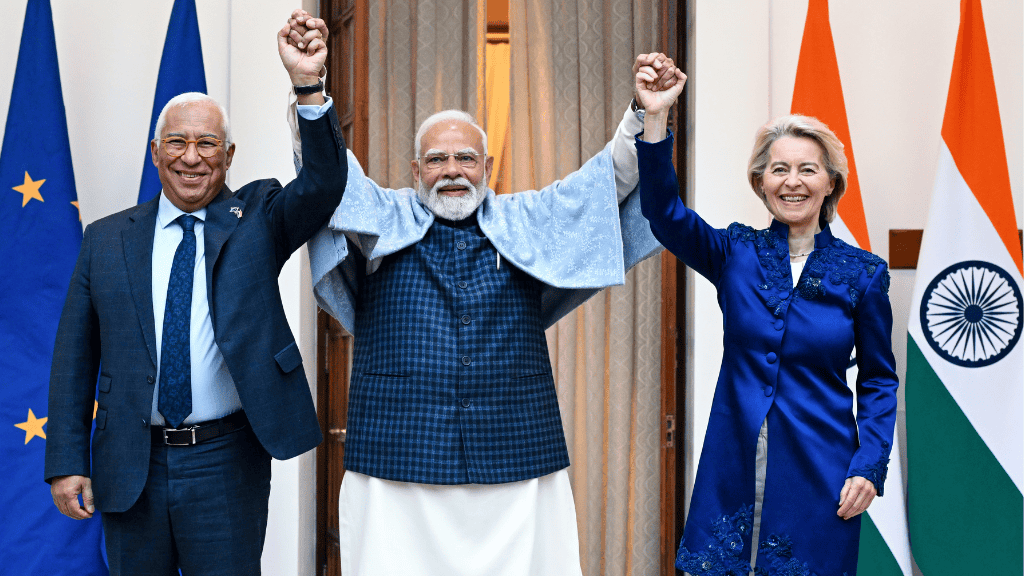

PM Narendra Modi (C) with the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen (R) and the president of the European Council, António Costa.

PM Narendra Modi (C) with the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen (R) and the president of the European Council, António Costa.

New Delhi: India and the European Union concluded a landmark free trade agreement on January 27, 2026, marking a watershed moment in global commerce after nearly two decades of intermittent negotiations. Announced during a state visit by the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, and the president of the European Council, António Costa, the deal has been characterized by the prime minister, Narendra Modi, as “the biggest free trade agreement in India’s history” and by von der Leyen as “the mother of all deals.”

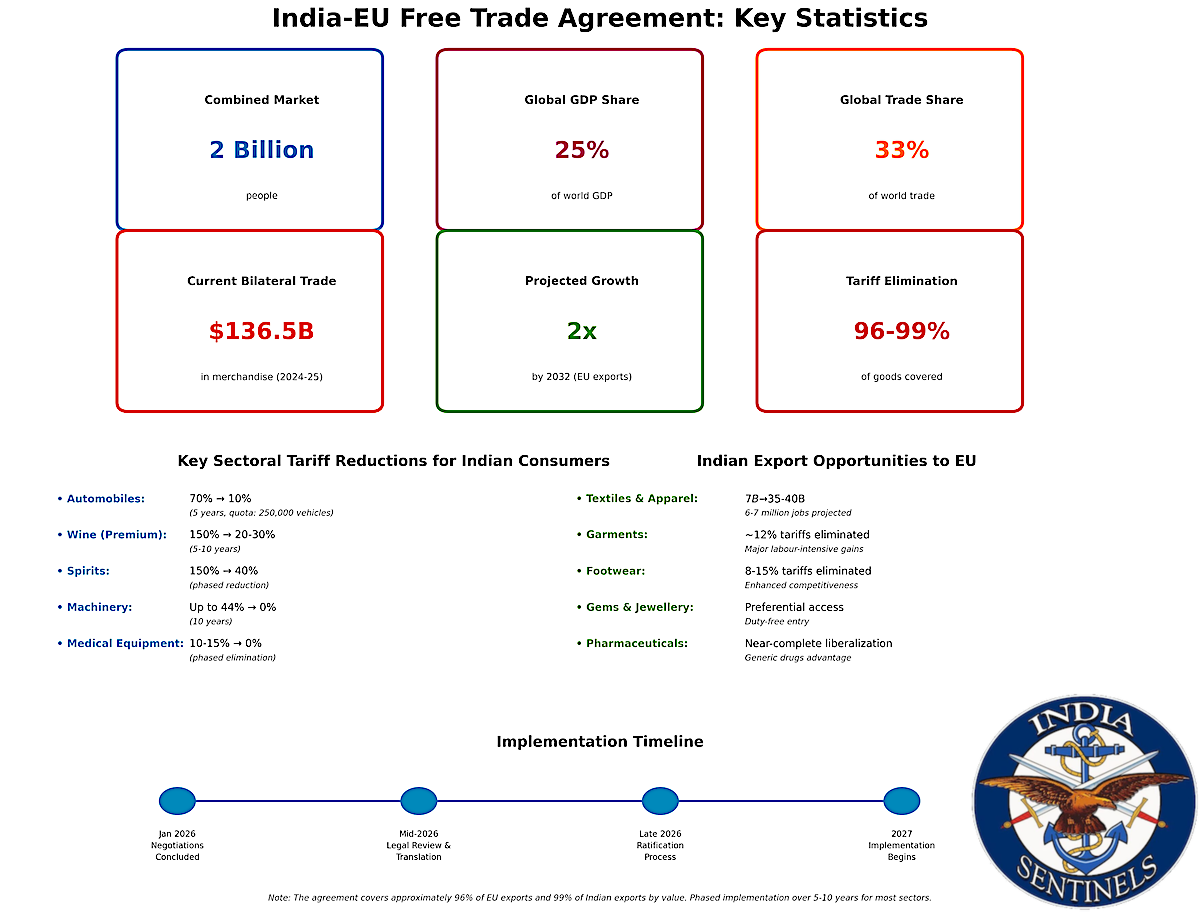

The agreement creates a unified trading bloc encompassing nearly 2 billion people and representing approximately 25 per cent of global GDP. It will eliminate or reduce tariffs on over 96 per cent of European exports to India and provide unprecedented market access for 99 per cent of Indian exports to the EU by value. Bilateral merchandise trade, currently valued at $136.5 billion, is projected to expand substantially, with EU exports potentially doubling by 2032.

The timing is significant. As protectionist headwinds intensify globally, particularly with the United States imposing 50 per cent tariffs on certain Indian exports, both India and the EU have positioned this agreement as a strategic counterweight, affirming their commitment to rules-based multilateral trade amid an increasingly fractious global environment.

The Long Road to Agreement

The India-EU free trade agreement negotiations began in 2007 with comprehensive ambitions spanning goods, services, investment protection, and intellectual property. However, talks stalled comprehensively between 2013 and 2019, seemingly abandoned amid irreconcilable differences over agricultural market access, automobile tariffs, regulatory standards, and intellectual property safeguards. The impasse reflected fundamental tensions: India sought protection for its agricultural sector and domestic manufacturing base, while the EU pressed for enhanced market access across multiple sectors and stronger intellectual property provisions.

In June 2022, both parties formally relaunched negotiations, accompanied by parallel discussions on investment protection and geographical indications agreements. The breakthrough reflected transformed geopolitical calculations on both sides. Rising protectionism, particularly from the Trump administration, supply chain vulnerabilities exposed by the Covid-19 pandemic, and intensifying competition from China accelerated recognition that India and the EU shared complementary economic interests and strategic imperatives.

The final phase of negotiations intensified through 2024 and 2025, with deliberate acceleration to reach conclusion by January 2026. The timing, coinciding with India’s Republic Day celebrations and the state visit of European leadership, underscored the diplomatic and symbolic significance both parties attached to the agreement.

Scale and Global Significance

The numerical magnitude alone distinguishes this agreement. The EU is India’s largest trading partner, with bilateral trade in goods reaching €120 billion in 2024, representing 11.5 per cent of total Indian trade. India is the EU’s ninth-largest trading partner, accounting for 2.4 per cent of the bloc’s total goods trade. While India’s share in EU trade remains modest compared with major partners like the United States (17.3 per cent), China (14.6 per cent), or the United Kingdom (10.1 per cent), the EU represents about 25 per cent of global GDP and roughly one-third of global trade.

Total EU services exports to India reached €26 billion in 2024, a figure expected to grow substantially under the new market access conditions. For India, between 2019 and 2024, bilateral trade in services grew steadily, with Indian exports rising from €19 billion to €37 billion. The combined consumer market encompasses 1.45 billion Indians and approximately 450 million Europeans, creating a unified trading zone unprecedented in bilateral trade agreements.

The European Commission estimates the deal will reduce tariffs on European products entering India by around €4 billion annually, providing substantial savings for European exporters. For India, the agreement opens preferential access to the world’s second-largest economic bloc at a critical juncture when export diversification has become strategically imperative.

India-EU Free Trade Agreement Key Statistics. (India Sentinels infographic.)

India-EU Free Trade Agreement Key Statistics. (India Sentinels infographic.)

Sectoral Tariff Architecture

The agreement’s transformative impact lies in sector-specific tariff reductions, each calibrated to reflect both developmental priorities and domestic sensitivities.

Automobiles and Components: India will progressively reduce tariffs on European passenger cars from the current 70 per cent to 10 per cent over a five-year transition period. However, this reduction operates under a critical quota mechanism: only 250,000 vehicles annually may enter at the reduced tariff, protecting India’s domestic automotive manufacturing base.

Furthermore, mass-market electric vehicles and vehicles priced below ₹25 lakh (approximately $30,000) remain explicitly excluded from preferential access, ensuring India’s burgeoning EV and affordable car segments remain insulated from European competition.

Automotive components, by contrast, face near-complete tariff elimination over ten years, reflecting recognition that India’s auto supply chain benefits substantially from duty-free access to advanced components and intermediate goods. Premium European brands like Lamborghini, which currently face significant import duties on vehicles starting around ₹3.8 crore, stand to benefit considerably from the reduced tariff regime.

Beverages and Agricultural Products: Wine tariffs, currently among the world’s highest at 150 per cent, will be dramatically reduced to 20–30 per cent for premium varieties over a phased 5–10-year period, though wines priced below €2.50 receive no concessions. Spirits including whisky, vodka, rum, and gin will see duties fall from 150 per cent to 40 per cent, while beer will drop from 110 per cent to 50 per cent.

These reductions will make premium European wines and spirits substantially more affordable, potentially transforming India’s premium beverage market, though phasing ensures domestic producers can adapt. Olive oil, currently taxed at 45 per cent, will achieve tariff-free status within five years.

However, agriculture remains one of the most sensitive areas, employing close to 44 per cent of India’s workforce, and broader EU access to Indian food markets has encountered strong domestic resistance. The European Commission has confirmed that several products, including dairy and sugar, fall outside the agreement’s scope.

Industrial Machinery and Chemicals: Industrial machinery currently facing tariffs up to 44 per cent will see most duties eliminated or phased down over 10 years, a critical development enabling India’s infrastructure and industrial expansion. Chemicals facing up to 22 per cent tariffs and pharmaceuticals at approximately 11 per cent will achieve near-complete liberalization.

This liberalization fundamentally strengthens India’s manufacturing competitiveness by reducing input costs for downstream producers while simultaneously enhancing India’s pharmaceutical exports, creating a complementary rather than competitive dynamic.

Aircraft and Medical Equipment: EU aircraft and spacecraft will achieve near 100 per cent tariff elimination, critical for India’s expanding aviation sector and space program. Medical equipment and diagnostic machinery, currently facing 10-15 per cent tariffs, will see near-complete duty elimination, potentially reducing healthcare costs and enhancing access to advanced medical technology across India’s healthcare infrastructure.

Services Liberalization: India’s Bold Commitment

Beyond tariff cuts on goods, the agreement marks a substantial breakthrough in services liberalization, with India’s services commitments the most ambitious it has ever undertaken, surpassing concessions granted to partners such as the United Kingdom and Australia. European companies will gain more predictable access to key sectors including financial services, maritime transport, and professional services, with clearer rules on licensing, local presence, senior management, and board requirements.

This liberalization holds particular significance for India’s information technology and business process services sectors, which have historically faced market access barriers in European markets. Enhanced mobility provisions for Indian professionals, clearer visa procedures, and recognition of qualifications could substantially expand India’s services exports, which currently constitute a significant portion of bilateral trade.

Indian Export Sectors: Labour-Intensive Gains

Since many EU duties were already relatively low, India’s main gains lie in labour-intensive sectors where tariffs remained high, particularly garments (around 12 per cent) and footwear (8-15 per cent), along with marine products, gems and jewellery, handicrafts, chemicals, and machinery.

The commerce and industry minister, Piyush Goyal, stated that India will receive unprecedented market access at concessional duties for over 99 per cent of its exports by value in the European Union market, providing a boost to domestic labour-intensive sectors. If textiles exports to the EU increase from the current $7 billion to about $35–40 billion, it would lead to fresh jobs to the tune of 6–7 million being created, he noted.

The Confederation of Indian Textile Industry stated the deal makes it possible for India to achieve textile and apparel exports worth $100 billion by 2030. Currently, the European Union is the second-biggest market for India’s textile and apparel exports, after the United States. The agreement is expected to provide Indian textile and apparel exporters with a level playing field against competitors from Vietnam and Bangladesh, which currently enjoy preferential access to European markets.

Other sectors poised for significant gains include leather and footwear, gems and jewellery, marine products, pharmaceuticals, and engineering goods. The tariff reductions will particularly benefit small and medium enterprises in these labour-intensive sectors, potentially catalysing employment generation across India’s manufacturing heartland.

Strategic Needs and Geopolitical Context

The agreement’s timing underscores both parties’ strategic calculations regarding the evolving global order. With elevated US tariffs reaching levels of up to 50 per cent in certain sectors, the agreement offers India an opportunity to reduce dependence on other economies and strengthen export competitiveness in Europe. For the EU, the deal provides strategic partnership with a rapidly growing economy while diversifying supply chains away from over-reliance on China.

Both von der Leyen and Modi explicitly framed the agreement as affirmation of commitment to rules-based multilateral trade at a time when protectionism threatens global prosperity. Von der Leyen stated the deal sends a signal to the world that rules-based cooperation still delivers great outcomes. Modi characterized it as not just a trade agreement but a new blueprint for shared prosperity.

The agreement also reflects India’s broader trade diversification strategy. Since 2014, India has finalized seven trade pacts, including with Mauritius, Australia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, the United Kingdom, the European Free Trade Association, and New Zealand. The EU agreement represents the most comprehensive and economically significant of these agreements, positioning India at the centre of multiple overlapping trade networks.

Implementation Timeline and Procedural Steps

While negotiations concluded on Tuesday, January 27, 2026, implementation requires substantial procedural steps. The agreement will undergo legal revision and translation into all 24 official EU languages, a process anticipated to require five to six months. The European Commission will then submit it to the Council and European Parliament for approval. In parallel, India must secure Union Cabinet approval and complete domestic ratification procedures.

Commerce officials expressed hope that the trade agreement will come into effect within calendar year 2026, though the complexity of tariff regime changes and ratification procedures could extend timelines. Once ratified by both sides, tariff reductions and regulatory provisions will be gradually phased in over a period of up to ten years.

Challenges and Unresolved Issues

Despite the agreement’s sweeping scope, significant challenges and unresolved issues remain.

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: A crucial issue is that the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is not addressed in the agreement. From January 1, 2026, EU imports are taxed based on carbon emissions. Although CBAM currently applies to only six products, including steel and aluminium, it is designed to expand to all industrial goods, potentially eroding much of the agreement’s tariff benefits. Indian exporters in high-emission sectors face potential carbon levies of 20–35 per cent, which could offset tariff gains and create additional compliance burdens, particularly for small and medium enterprises.

Non-Tariff Barriers and Regulatory Compliance: Sanitary and phytosanitary standards, traceability requirements, and sustainability certifications constitute formidable barriers despite tariff elimination. Agricultural exporters must invest substantially in compliance infrastructure, digital traceability systems, and third-party verification – barriers that tariff reduction does not address. European regulatory standards for food safety, labelling, and environmental sustainability remain among the world’s most stringent, potentially limiting actual market access for Indian agricultural exporters despite nominal tariff reductions.

Domestic Competition Pressures: Indian manufacturers in automobiles, machinery, chemicals, and medical devices will face intensified competition from European producers with superior technology, capital resources, and established brands. While protective mechanisms like quotas and exclusions provide breathing room for domestic industries, successful competition will ultimately require continued innovation, productivity enhancement, and scale economies. The transition period will test the resilience and adaptability of Indian manufacturing across multiple sectors.

A New Chapter in India-EU Relations

The India-EU free trade agreement announced on Tuesday represents a historic milestone in global commerce, establishing a trading bloc encompassing 2 billion people and transcending traditional regional configurations. For India, the agreement provides transformative market access for labour-intensive sectors, particularly textiles, pharmaceuticals, engineering goods, and services. For the EU, it opens access to the world’s fastest-growing major economy, enabling European technology and capital goods exports while providing supply chain diversification alternatives to China.

Critically, the agreement emerges as a statement of intent by two major democracies regarding the future of global trade. Against rising protectionism and unilateral tariff actions, the India-EU agreement affirms commitment to rules-based, reciprocal trade that benefits both parties through structural complementarity rather than competitive displacement. Implementation by late 2026 or early 2027 will require navigating procedural complexities and addressing challenges like the carbon border adjustment mechanism and regulatory compliance barriers.

Yet the political will appears firmly established. As Modi stated, this transcends conventional trade arithmetic to represent strategic partnership between two democratic economies determined to shape a more open, stable, and prosperous global trading system.

Whether the agreement delivers on its ambitious projections will depend not only on tariff reductions but on both parties’ ability to address non-tariff barriers, facilitate regulatory convergence, and manage domestic adjustment pressures.

The next few years will prove decisive in determining whether this truly is, as von der Leyen proclaimed, the mother of all deals.