Narendra Modi (R) with Vladimir Putin at Hyderabad House in New Delhi, on December 5, 2025. (Photo: PMO)

Narendra Modi (R) with Vladimir Putin at Hyderabad House in New Delhi, on December 5, 2025. (Photo: PMO)

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s recent two-day state visit to New Delhi has been hailed by both governments as a landmark moment in the India-Russia strategic partnership. The 23rd Annual Summit produced impressive-sounding outcomes: the Reciprocal Exchange of Logistics Support (RELOS) agreement, a roadmap for $100 billion in bilateral trade by 2030, and commitments to transform defence cooperation from a buyer-seller relationship into joint co-development.

The optics were carefully choreographed, the joint statements effusive, and the diplomatic messaging clear. Yet, having spent nearly four decades commanding troops along the line of actual control (LAC), serving UN missions abroad, and studying the hard realities of strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific, this author must ask: was this visit more about geopolitical signalling than substantive transformation?

The answer, this author would argue, is a resounding yes – at least for now. This is not to diminish the importance of the summit, but rather to inject a dose of realism into the analysis. Both India and Russia had compelling reasons to showcase their partnership at this particular moment, and the visit served critical signalling functions for each. However, the gap between promise and delivery, between intent and implementation, remains vast.

Let us examine what was truly achieved, what remains aspirational, and why this visit tells us more about current geopolitical anxieties than future strategic certainties.

Read also: Pakistan’s Last Refuge – Nuclear rhetoric after military defeat

Geopolitical Context: Why Now?

To understand this summit, one must first appreciate the timing. For Russia, isolated by western sanctions and fighting a protracted war in Ukraine, demonstrating continued relevance and partnership with a major global power like India was diplomatically essential. Putin’s ability to visit New Delhi, receive a warm reception, and sign multiple agreements sends a message to Washington and Brussels: Russia is not isolated, and its pivot to Asia is bearing fruit.

India, with its growing economy and significant energy imports from Russia, provides Moscow with both economic lifeline and diplomatic validation.

For India, the calculus is different but equally compelling. New Delhi finds itself navigating an increasingly complex strategic environment. To the north, China’s assertiveness along the LAC remains undiminished despite multiple rounds of military and diplomatic talks. Beijing’s deepening entente with Moscow creates a Eurasian axis that India cannot ignore. To the east and south, India’s partnerships with the United States, Japan, and Australia through the Quad framework are deepening, yet these relationships bring expectations of alignment that New Delhi is reluctant to fully embrace.

Hosting Putin and reaffirming the “special and privileged strategic partnership” with Russia serves as a powerful assertion of India’s strategic autonomy – a message directed as much at Washington as at Beijing.

This is where the signalling aspect becomes paramount. India’s foreign-policy establishment has long prided itself on maintaining strategic independence, refusing to be boxed into Cold War-style blocs. By deepening ties with Russia even as it strengthens its security cooperation with western powers, India demonstrates that it will not be constrained by others’ binary choices.

This is smart diplomacy, but it should not be confused with substantive strategic transformation.

Read also: Thank you, Trump, for making India understand America like never before

RELOS Agreement

The centrepiece of this visit, at least in strategic military terms, was the operationalization of the RELOS agreement. Signed in Moscow on February 18, 2025, and ratified by Russia’s State Duma on December 2, just days before Putin’s arrival, this reciprocal logistics support pact grants Indian and Russian armed forces access to each other’s military ports, airbases, and logistical infrastructure for refuelling, berthing, supplies, and repairs.

On paper, RELOS is transformative. It provides India with potential access to Russian facilities in the Arctic and the Pacific, particularly Vladivostok, while giving Russia access to Indian naval bases in the Indian Ocean. For a navy that has long aspired to blue-water capabilities, the prospect of operating in the Arctic’s Northern Sea Route or having a forward logistics hub in Vladivostok is tantalizing. India already has similar agreements with the United States (LEMOA), France, Japan, and Australia. Adding Russia to this list theoretically enhances India’s operational flexibility across multiple theatres.

However, having commanded forces in some of India’s most strategically sensitive regions and a keen student of geopolitics, this author is compelled to ask: how operationally relevant is RELOS in practice? Let us consider the realities.

Read also: How Trump lost India – and why America must win it back

First, the Arctic. While climate change is indeed opening new maritime corridors in the region, India’s immediate strategic interests remain firmly anchored in the Indian Ocean Region and, increasingly, the western Pacific. The idea of Indian naval vessels regularly patrolling the Northern Sea Route, thousands of miles from our primary areas of interest, strikes me as more aspirational than operational. What specific Indian national security interest does an Arctic presence serve?

Beyond symbolic presence and potential commercial shipping route security, the strategic rationale remains unclear.

Second, Vladivostok. Here, the utility is more apparent but still constrained. India’s eastern fleet could indeed benefit from a forward logistics hub in the Pacific, particularly as we seek to expand our strategic footprint and engage more actively with Asean and East Asian partners. Yet, Russia’s own Pacific fleet is not what it once was, and Vladivostok’s infrastructure and strategic posture are oriented towards Russia’s own regional challenges, particularly vis-à-vis Japan and the United States.

Moreover, in any scenario where India might genuinely need such access – say, a major crisis involving China – would Russia’s ports actually be available, or would Moscow’s own complex relationship with Beijing constrain our access?

Read also: Charting India’s Strategic Autonomy – A perspective on geopolitical reset

Third, and most critically, RELOS is explicitly not a basing agreement. It provides case-by-case access, not permanent facilities or pre-positioned assets. This means that in a crisis, when such access would be most needed, it would require diplomatic negotiations and Russian approval. Compare this to the practical operational integration India has achieved with the United States through LEMOA, COMCASA, and BECA – agreements that enable real-time intelligence sharing, encrypted communications, and near-seamless logistical cooperation during exercises and potential contingencies.

RELOS, therefore, is best understood as a strategic hedge and a political statement rather than a transformative operational capability. It diversifies India’s options, prevents over-reliance on western partnerships, and signals to all parties that India maintains relationships across the geopolitical spectrum. These are valuable outcomes, but they are primarily about signalling strategic autonomy rather than acquiring substantive new military capabilities.

Read also: As Sergio Gor lands, India must map its own course amid Trump’s SA reset

Economic Ambition Meets Reality

The economic component of the summit – the programme to reach $100 billion in bilateral trade by 2030 – similarly exemplifies aspiration over immediate substance. Bilateral trade stood at $68.7 billion in March this year, heavily skewed towards energy imports. Russia supplies approximately 40 per cent of India’s crude oil imports, a relationship that has deepened significantly since western sanctions created opportunities for discounted Russian energy. This energy trade is transactional and driven by economic pragmatism rather than strategic partnership per se.

The roadmap promises diversification into fertilizers, precious metals, minerals, agriculture, healthcare, and critical raw materials. It commits to fast-tracking an India-Eurasian Economic Union free trade agreement and a new bilateral investment protection agreement.

These are worthy goals, but several obstacles loom large.

First, the structural composition of India-Russia trade remains problematic. Beyond energy and defence, economic complementarities are limited. Russia is not a major source of advanced technology or manufacturing inputs that India’s economy increasingly requires. Indian exports to Russia – primarily pharmaceuticals, tea, and some manufactured goods – face their own market access challenges.

Second, the payment mechanism problem persists. Both countries have discussed creating a “third-country-proof”, non-dollar payment system to circumvent sanctions, but such mechanisms are complex to operationalize at scale. The rupee-rouble trade settlements that have been attempted face convertibility issues and are insufficient for large-scale commerce.

Third, logistics infrastructure remains inadequate. The International North-South Transport Corridor and the Chennai-Vladivostok Maritime Corridor are frequently mentioned but remain underdeveloped. Without efficient, reliable transport links, trade expansion will be constrained by physical bottlenecks and higher transaction costs.

Read also: Amnesia vs Engagement – A soldier’s view on India’s China dilemma

The labour mobility agreement is interesting but limited in scope. Russia’s demographic challenges and labour shortages are real, and Indian skilled professionals could fill gaps in sectors like IT and healthcare. However, the scale of such movement and its economic impact remain to be seen. This is a useful initiative but not a game-changer in bilateral economic relations.

In essence, the $100 billion trade target is aspirational rather than inevitable. It requires sustained political will, significant infrastructure investment, and resolution of structural impediments – none of which are guaranteed. Without concrete implementation timelines and measurable interim targets, such announcements risk becoming rhetorical devices rather than actual policy.

Defence Buyer-Seller to ... What Exactly?

The stated shift in defence cooperation from a simple buyer-seller relationship to joint co-development and co-production has been discussed for years. This summit reiterated that commitment, emphasizing joint research and development in hypersonic systems, unmanned aerial vehicles, and aircraft engines, as well as establishing joint ventures for manufacturing spare parts in India.

This evolution is both necessary and overdue. India’s defence inventory is approximately 60 per cent Russian-origin equipment, much of it aging. Maintenance, spare parts, and upgrades have become increasingly challenging, particularly as Russia’s own defence industrial base has been strained by the war in Ukraine. Localizing production of spares and components makes operational sense and aligns with India’s “Make in India” initiative.

Read also: India’s Eastern Front – The new battleground that could eclipse Pak

However, several realities temper optimism. First, genuine co-development of advanced systems requires technological parity, trust, and complementary capabilities. India’s defence R&D ecosystem, while improving, still lags behind global leaders. Russia, facing its own technological constraints and western sanctions on key components, may have limited capacity for truly cutting-edge joint development in areas like hypersonics or next-generation UAVs.

Second, intellectual property concerns and technology transfer issues have plagued India-Russia defence cooperation for decades. The BrahMos missile programme, often cited as a success story, took years to mature and faced numerous bureaucratic and technological hurdles. Scaling such models across multiple platforms is non-trivial.

Third, India’s defence diversification strategy increasingly looks westward and inward. Major recent acquisitions have included American maritime patrol aircraft, French Rafale fighters, and Israeli drones, while indigenous programmes like the Tejas light combat aircraft and Arjun tank receive priority. Russia’s share of India’s defence imports has been declining, a trend unlikely to reverse dramatically.

The defence relationship will remain significant, but the transformation from buyer-seller to equal partners in co-development is aspirational. Incremental progress – joint ventures for spares, limited co-production – is realistic. Revolutionary change in the near term is not.

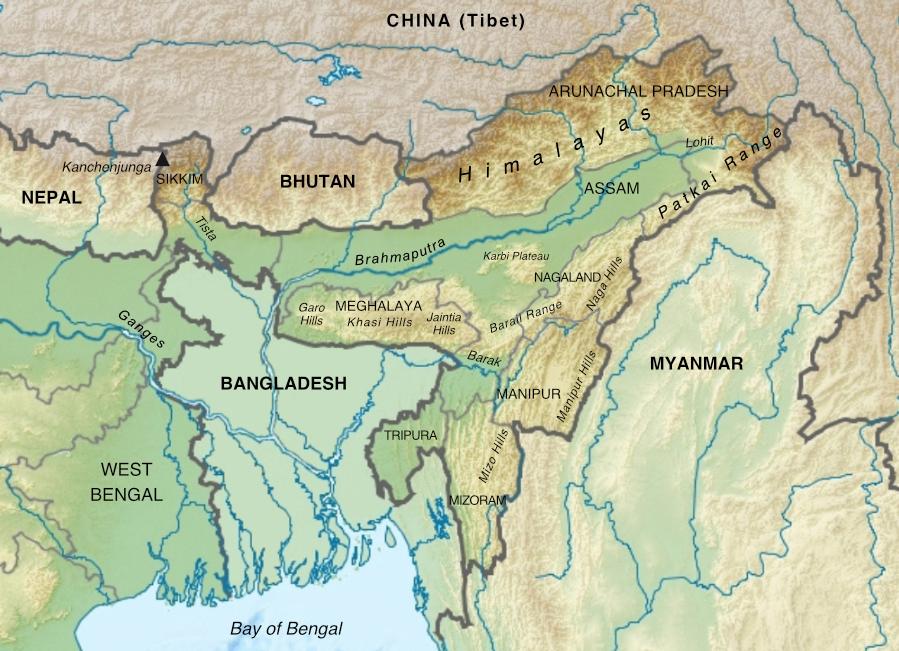

Read also: China’s Brahmaputra Gambit – A strategic assessment of Motuo dam

What This Means for India?

So where does this leave us? Putin’s visit achieved its primary purpose: signalling strategic autonomy and demonstrating that India will not be pressured into exclusive partnerships. For Russia, it provided much-needed diplomatic validation and a showcase partnership amid isolation. For India, it reinforced multi-alignment as the core of its foreign policy.

However, from a hard-nosed strategic perspective, the outcomes remain more potential than actual. RELOS provides theoretical access to Russian facilities but limited operational utility in scenarios most likely to threaten India’s core interests. The economic roadmap sets ambitious targets but offers few concrete mechanisms to overcome structural impediments. Defence cooperation promises transformation but will likely deliver incremental change.

This is not necessarily a criticism. Geopolitical signalling has value in itself. In an era of great power competition, where alignments are fluid and strategic autonomy is precious, demonstrating the capacity to maintain relationships across divides serves Indian interests. The visit reinforced that India is not a junior partner in anyone’s strategic framework but a sovereign power pursuing its own interests.

Yet, as someone who has spent a career studying and confronting real strategic threats – particularly from China along our contested border – this author remain focused on deliverables rather than declarations. The true test of this summit will come in the years ahead. Will RELOS facilities actually be used? Will trade approach the $100 billion target? Will joint defence ventures produce tangible outcomes? Will Russia remain a reliable partner as its own strategic calculations evolve in response to the war in Ukraine and its deepening dependence on China?

Read also: Network-Centric Warfare – Pakistan’s edge and India’s wake-up call

These are the questions that matter. For now, Putin’s visit was a successful exercise in diplomatic theatre – important, symbolically valuable, and strategically astute. But until promises translate into practice, we should recognize it for what it was: signalling over substance, aspiration over achievement. And in the unforgiving arena of great power competition, signalling alone does not guarantee security or prosperity. Implementation does.

India’s strategic future depends on our ability to transform diplomatic rhetoric into operational reality, to convert partnerships on paper into capabilities on the ground. The summit provided the framework. The hard work of building substance behind the signalling begins now.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect the views of India Sentinels.

Follow us on social media for quick updates, new photos, videos, and more.

X: https://twitter.com/indiasentinels

Facebook: https://facebook.com/indiasentinels

Instagram: https://instagram.com/indiasentinels

YouTube: https://youtube.com/indiasentinels

© India Sentinels 2025-26