The Rezang-la War Memorial. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

The Rezang-la War Memorial. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

“We carved not a line, and we raised not a stone,

But we left him alone in his glory.”

~ Charles Wolfe

After the eight-day battle, which concluded on October 27, 1962, there was an eerie silence in Ladakh until the early hours of November 18 when an artillery shell landed and broke the silence, thus ushering in some of the most famous battles in military history.

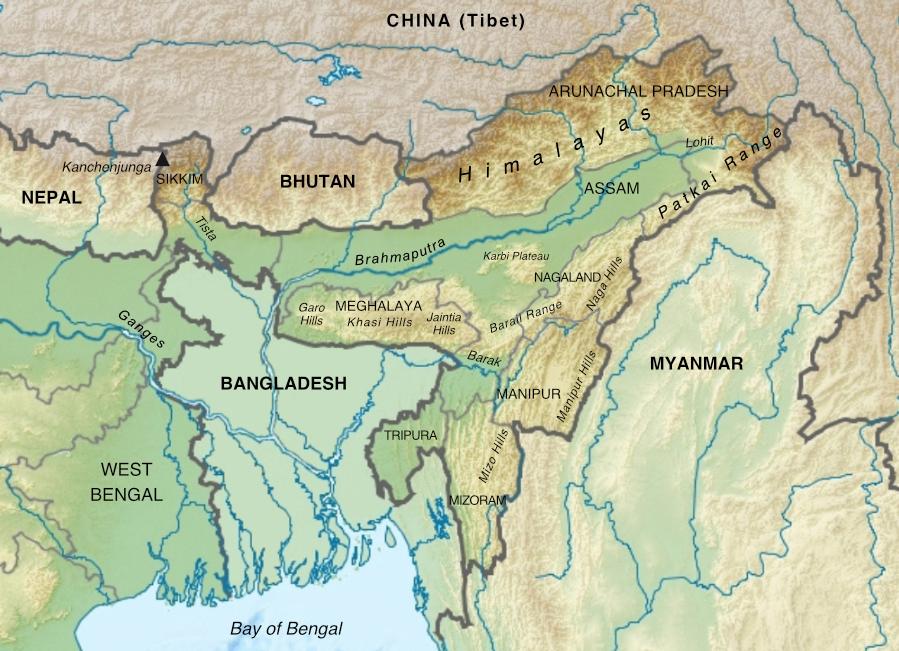

The Chushul sector is in the south of the Chang-Chenmo valley and has Pangong-tso as its main attraction. The village of Chushul is located to the west of the vast Spanggur Gap – a mountain pass on the line of actual control (LAC) between India’s Ladakh and China-controlled Tibet’s Rutog county in Ngari prefecture, which is located on the west side of the Spanggur lake and has a mountain slope on its south bank. The Chushul airstrip, which is strategically significant, is located between the village and the gap. On this airstrip, Indian Air Force’s An-12 and Packet planes used to land frequently.

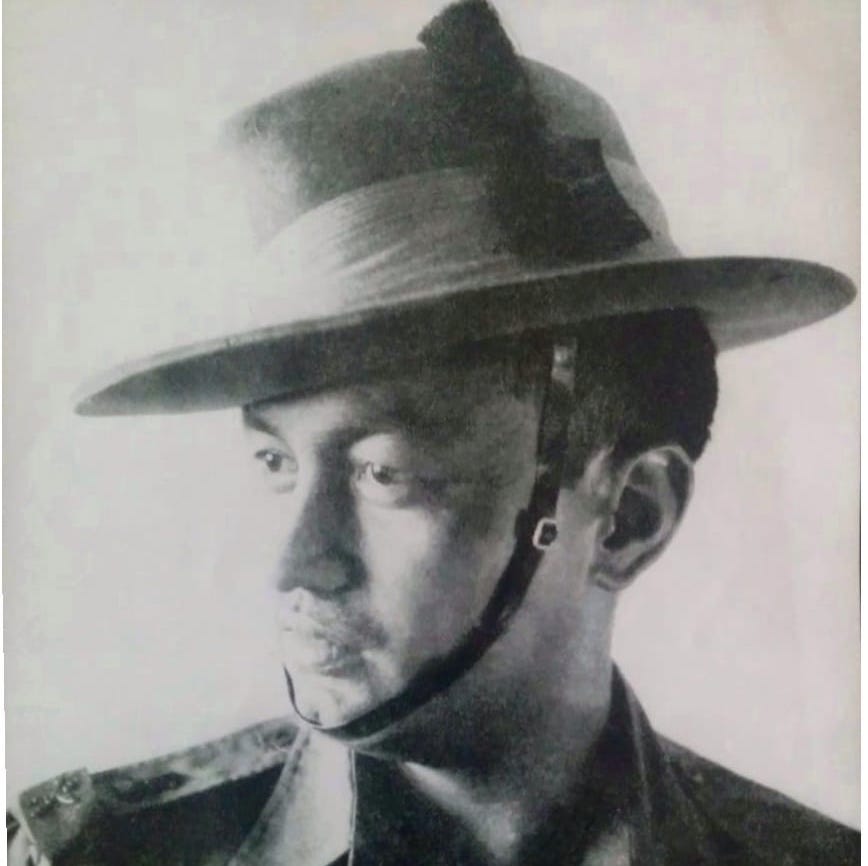

Chushul was held by two companies of the 1/8 Gorkha Rifles when the India-China conflict began. Its Delta Company’s lesser platoon, led by Maj Dhan Singh Thapa, was stationed at the Sirjap complex, which was maintained by assault boats and had no land connection to the Chushul garrison.

Maj Dhan Singh Thapa. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

Maj Dhan Singh Thapa. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

The Yula complex was located at the south of the Pangong-tso (Pangong lake). It was manned by a company of the 1/8 GR. The remaining two companies were sent to defend the Spanggur Gap. The company positions – Sirjap I and Sirjap II – were on the north and south shoulders of the Spanggur Gap named Gurung Hill and Magar Hill respectively, with a post in the gap as well. The posts, Gurung Hill and Magar Hill, were named after the main subcastes of the unit’s troops.

Since September that year, the Chinese had surrounded the Sirjap complex, which included the company positions at Sirjap I and II. The complex was on the other bank of the Pangong-tso and was totally maintained by boats.

The enemy prepared itself well since it had direct road linkages to Sirjap with the Khurnak fort. This made it simpler for them to transport reinforcements, supplies, and heavy weapons. On the other hand, the Indian forces only had personal weapons and light machine guns (LMGs), and the lake served as the only supply line.

The Chushul battlefield, as it looks today. (Photo: India Sentinels/Jai Samota)

The Chushul battlefield, as it looks today. (Photo: India Sentinels/Jai Samota)

The Battle of Sirjap

Maj Thapa’s company was in the Sirjap area, near the Pangong-tso, and was supplied and maintained by assault boats. Chinese soldiers used artillery and mortars to attack the Indian Army position of Sirjap I early on October 21. Consequently, the Gorkha troops were severely injured. At this juncture, Chinese troops began to progressively approach the Indian stronghold. The Chinese soon came up with light tanks against which Indian troops had no weaponry. Then, Chinese forces launched an overwhelming assault on Maj Thapa’s isolated company.

The Gorkhas responded and repulsed three enemy attacks. Unfortunately, Thapa’s company suffered greatly during this conflict, and just seven of his 28 troops survived. After a while when the Indian soldiers’ ammunition ran out, the Gorkhas yelled “Jai Maa Kali Aayo Gorkhali”, their war cry, and attacked the Chinese with their khukris.

However, Sirjap I fell to the enemy due to the larger size of the enemy forces. After overpowering the Indian forces with their numerical superiority, the Chinese captured Maj Thapa as a prisoner of war. Since there was no connection with the post, the battalion headquarters dispatched one patrol led by Nk Rabi Lal Thapa (who was later awarded the Maha Vir Chakra). The boat got as near as 1,000 yards to the position before being fired upon by the enemy, so it turned around and reported that the entire post had collapsed, assuming Maj Thapa and his men had been killed.

Then, after a fierce battle, the Chinese also took over Sirjap II. And by October 22, all forward posts in the Chushul sector had been either withdrawn or overwhelmed by the enemy.

The Indus Valley

The Indus Valley is located south of Chushul in the southern sector. It was an important location since it had a route that connected Chushul to Dungti and then south to Demchok. Lt Col RM Banon*, commanding officer of the 7 J&K Militia, was in charge of the subsector’s defence. The unit had its headquarters in Koyul with a company, and troops of a company strength stationed in Dungti. The rest of the battalion was dispersed in small posts along the passes.

On October 27, the Chinese began attacking posts in the southern sector, following identical attack tactics which they used in northern and the middle sector.

Read also: ‘Death Trap’: The 1962 operation in Galwan-Chang Chenmo sector

The Battle of Chang-la

The Chinese forces assaulted the Chang-la post on October 27. Indian soldiers, numbering just 17, held the post against the larger enemy and prevented the post from being captured. However, with ammunition running low and Chinese strength building, it was becoming harder to uphold the post. At one point, the post commander, who was a junior commissioned officer (JCO), ordered his troops to withdraw while he kept providing cover fire with his LMG. The escaping troops made it to nearby Fukche. However, the post commander, who assisted his comrades in escaping, fell to enemy fire.

The Battle of Jara-la

The Chinese, together with Chang-la, encircled the post at Jara-la. There were also 17 men under the command of a non-commissioned officer (NCO). Over 300 Chinese troops marched up to the position and surrounded it in the morning. The Chinese encircled the post all day, but Indian troops managed to escape during the night, although one soldier was killed and seven were taken prisoner.

Other positions in the region were similarly besieged and overwhelmed by the Chinese. Sep Sonam Rabgais was on one of these posts when it was bombarded by the Chinese. He fought valiantly and remained in his trench until he was killed in action. He was later awarded the Vir Chakra.

Most of the Indian troops in the sector were asked to withdraw. The withdrawal commenced on the intervening night of October 27-28 and troops successfully managed to reach Koyul.

The Lull

There was no fighting in the Chushul sector after the forward posts fell. The Chinese also proposed negotiations with the Indian government. At this time, the Indian Army strengthened its foothold in the Ladakh theatre. At this time, the 114 Brigade, which was based in Leh, was moved to Chushul and became responsible for the Lukung-Phobrang-Chushul region.

Maj Gen Budh Singh raised the 3 Himalayan Division, on October 26, with 70 Infantry Brigade and 163 Infantry Brigade under its command. The sector also received one field artillery regiment, two tank troops, one heavy mortar battery, and field engineers.

Now, the 14 J&K Militia, which was formerly under 114 Brigade and was responsible for the northern sector or Saser-la-Shyok-Thoise, directly came under command of 3 Himalayan Division.

During the lull in fighting, the geography of the deployments underwent a big change.

The central or middle sector was held by the 114 Brigade, which was in charge of the Lukung-Chushul-Tsaka-la stretch. With four regular infantry battalions, 1/8 GR, 5 Jat, 13 Kumaon, and 1 Jat Light Infantry, two tank troops of 20 Lancers, the 38th Field Battery of 13 Field Regiment, one troop of 32 Heavy Mortar Battery, one company of field engineers, and one company of 1 Mahar with medium machine guns (MMGs), the brigade was now in a strong position.

The southern sector, which included Demchok-Dungti, was now under the command of Brigadier Rawind Singh Grewal, MC. He led the 70 Infantry Brigade with three infantry battalions and 7 J&K Militia battalion, as well as one battery of field regiment, one heavy mortar troop, one company of engineers, and one company of MMGs.

The Leh sector, which had previously been the headquarters of 114 Brigade, was now under the command of 163 Infantry Brigade, which had one field battery with regiment headquarters, one troop of heavy mortars, and one engineer company.

Except the 114 Brigade, no other formation in Ladakh had tank troops.

New deployment of 114 Brigade in Chushul

Initially based in Leh, the 114 Brigade was responsible for a vast frontage stretching from Daulat Beg Oldie (DBO) to Demchok with just two regular infantry battalions and two J&K Militia battalions, with no artillery or armoured support. Nevertheless, with the formation of the 3 Himalayan Division, the brigade’s area of responsibility reduced. Its operational area was now around 80 kilometres long, stretching from Lukung to Tsaka-la.

Read also: ‘Gateway to Hell’: The 1962 operation in Daulat Beg Oldie

The 5 Jat under Lt Col Bakhtawar Singh, which had been hard hit and sustained casualties in the DBO and Galwan sectors, was now regrouped and strengthened by troops from the Jat Regimental Center and other sister battalions. The battalion was now based in Lukung-Phobrang, and its Alpha Company, with lesser troops, was sent to Tsaka-la under the command of Lieutenant Prem Singh. The battalion was also supported by a troop of 32 Heavy Mortar Battery.

The 1/8 GR under Lt Col Hari Chand, the first battalion to move to Ladakh in 1961 was now without its Delta Company, which they lost in the Battle of Sirjap, were given the responsibility with one company each at Gurung Hill, Table Top-Camel’s Back and Spanggur Gap.

The 1 Mahar Y Company (MMG) under Maj Reddy*, was part of the brigade for a long time. It had participated in the first phase in DBO, now it moved to Chushul and was located at important positions.

The 13 Kumaon, which arrived at Baramulla in June under the command of Lt Col Hari Singh Dhingra under the 19 Infantry Division for its field tenure, was given orders on the final day of September to move to Leh by road. The battalion advance and main arrived in Leh on October 2 and were instructed to acclimatize while the battalion rear, led by the quartermaster, Maj Shaitan Singh, remained in Baramulla to transfer over duties.

On October 17, shortly after acclimatization, the unit received orders to move to Chushul. The advance party, led by Lt Prem Kumar, arrived at Chushul on the 24th and by 26th whole 13 Kumaon was inducted into the brigade. The 13 Kumaon headquartered near the airfield.

Lt Prem Kumar was given orders to deploy Charlie Company to Rezang-la and establish company positions. While Bravo Company, led by Capt HS Chauhan, and Delta Company, led by Capt Raghunath V Jatar, were sent to Magar Hill, the south shoulder of the Spanggur Gap. Capt Jatar was promoted to the rank of major and assigned charge of the post commander Magar Hill.

Maj Girish Narayan Sinha, the unit’s second in command (2IC), was also in command of the Alpha Company that served as a brigade reserve. Soon on October 27, Maj Shaitan Singh arrived at Chushul and he was ordered to hand over responsibilities of QM to Captain Gurdeep Singh and move to Rezang-la as Charlie Company Commander. Lt Prem Kumar who was commanding the company at Rezang-la was sent to Magar Hill.

Maj Shaitan Singh. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

Maj Shaitan Singh. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

The 20 Lancers, following the spread of the word that the Chinese were operating tanks in the region, the Indian Army began to induct tanks to confront the Chinese threat. Lt Col Gurbachan Singh “Butch” commanded the 20 Lancers, which was based in Ferozepur, Punjab, and was chosen for the assignment. Two tank troops with the squadron headquarters were transported to the Chandigarh airbase from where the tanks were to be flown in the-then newly inducted An-12 aircraft of the Indian Air Force’s 44 Squadron.

The trial to load tanks into aircraft began. However, due to the weight and structure of the tanks, the first trial failed, damaging the aircraft. With the assistance of local carpenters, a suitable ramp, adequate floor, and tail support for the aircraft were quickly constructed, with sandbags acting as shock absorbers. Sqn Ldr Chandan Singh, an accomplished aviator, was responsible for landing the tanks at the Chushul airstrip.

With the additional load from the tanks in mind, he took the risk and cut the aircraft fuel to half to finish the Chandigarh-Chushul-Chandigarh flight. He successfully landed the tanks at Chushul without any damage to aircraft.

The squadron commander and two other officers were evacuated shortly after landing at Chushul owing to high altitude sickness, but Lt Avinash Chand, a tank commander, refused to be evacuated. Capt Ashwani Kumar Dewan was now in command of both the troops and the squadron headquarters.

Read also: ‘Honour, Enfield, and Panama’: The story of Lt Yog Raj Palta

The tanks were now positioned near the foot of Gurung Hill at a position where the enemy couldn’t see them. That was the first time Indian tanks had been transported to such altitudes. It was extremely difficult to operate tanks due to the weather and a lack of oxygen.

The 13 Field Regiment, which was led by Lt Col Shri Dhar Man Singh, was stationed somewhere in the Kashmir valley. Lt Col Dhar was asked to move quickly by road from Srinagar to Leh. The regiment was headquartered in Leh, and its two batteries were transported to Chushul and Dungti under the 114 Brigade and 70 Brigade, respectively.

Maj SP Joshi led the 38th Field Battery, which was moved to Chushul. The battery had two troops, each one with four 25-pounder guns. All the guns were positioned at the base of Gurung Hill and Magar Hill to support both the hill features and the Spanggur Gap. Rezang-la was left isolated since the gun behind Magar Hill was unable to support it owing to crest clearance issues. The battery had two observation posts, one at Gurung Hill and the other at Magar Hill with Capt AD Singh* and Capt Sharma being observation post officers.

The 1 Jat Light Infantry battalion was in the same formation as 13 Kumaon in the Uri sector, but the latter was transferred first in October, and the Jats were given the order to move in November. In just a few days, the entire battalion assembled at the Srinagar airbase, from where they were flown and transported to Chushul under the command of Lt Col Jaspal Singh.

After being inducted into the sector without acclimatization, troops began to experience difficulties. Soon, a JCO died of altitude sickness and the commanding officer had to be evacuated due to pulmonary edema. Lt Col Balbir Singh was appointed to command the unit.

The unit’s Alpha Company was led by Capt Kuldeep Singh Kang, who was also serving as the unit’s adjutant, and the Charlie Company was commanded by Maj Ranjit Singh Mavi. They were deployed at the brigade depth near the battalion headquarters at Chushul. The Bravo Company, commanded by Lt Surjit Singh Kler, was deployed at Thankung and Yula, while the Delta Company, commanded by Maj Sukhwinder Singh Malik, was stationed at Lukung on the shores of Pangong-tso.

With its two battalions, which incurred serious casualties in the initial phase of the war, and 14 J&K Militia, which has been placed directly under the command of 3 Himalayan Division, and 7 J&K Militia, which has been transferred under the command of 70 Infantry Brigade, the 114 Brigade was short on manpower.

With the addition of support components and two additional infantry battalions, the brigade quickly gained strength, and the commander began reconnaissance and siting operations. With frequent reconnaissance, good tactical positions for tanks, artillery, and infantry were identified. Troops were sent to their assigned areas, and digging for trenches and weapon pits began.

During the first week of November, all battalions and units had been deployed and were combat ready. The brigade commander visited posts at Rezang-la, Magar Hill, and Gurung Hill on a regular basis to acquire first-hand information of the enemy’s development and movement.

No aggressive activity from the Chinese side was recorded in November. However, they had a build-up at the Spanggur lake, which was connected by road from Rudok and Khurnak fort, making it simpler for them to transfer weapons and other logistical supplies. The Charlie Company at Rezang-la had no artillery support but was aided by 3-inch mortars – the battalion’s main weapon. Maj Shaitan Singh led the company and was in contact with the battalion headquarters.

In the evening of November 17, the adjutant of 13 Kumaon, Capt DD Saklani*, contacted Maj Shaitan Singh. The situation was calm at the time. Later that night, at around 10pm, he called again, and the radio operator told him that the situation was normal. It was Capt Saklani’s last call to the Charlie Company after the communication lines were disconnected.

In the early morning of November 18, the Chinese artillery began bombarding the Indian positions at Rezang-la, Magar Hill, Gurung Hill, and the battalion’s headquarters of 13 Kumaon.

The Battle of Chushul had begun.

***

The Battle of Chushul comprises the Battle of Rezang-la and the Battle of Gurung Hill with actions of artillery and armoured troops.

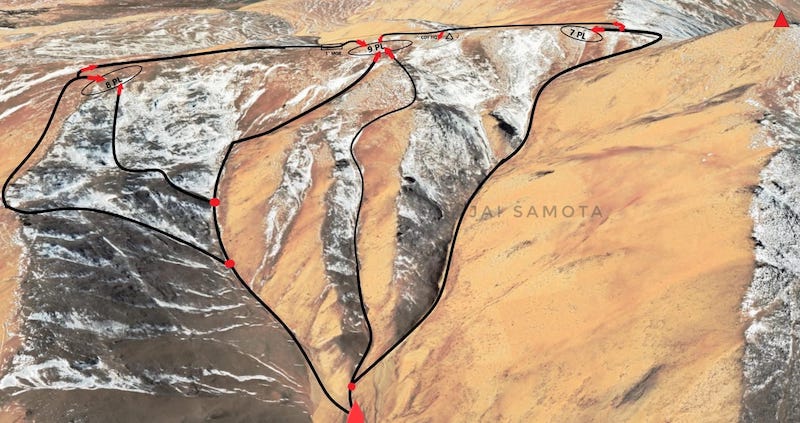

The Battle of Rezang-la

Rezang-la is a massive feature with a height of approximately 5,180 metres. It was defended by the 13 Kumaon’s Charlie Company. Deployed over a stretch of about two kilometres, it had a strength of 127 soldiers of all ranks. The company consisted of No. 7, 8 and 9 platoons. The ground required to cover at Rezang-la was much larger than what could be covered by the troops available there, at that time.

The author pointing towards the Rezang-la feature. (Photo: India Sentinels/Jai Samota)

The author pointing towards the Rezang-la feature. (Photo: India Sentinels/Jai Samota)

The company administrative base, with its cook house, reserve rations, and clothing were located at the nallah (rivulet) below. The company position had been prepared well within the time limits and resources available.

On the intervening night of November 17-18, at around 10pm, a heavy snowstorm lashed the battlezone for nearly two hours. After the storm, visibility improved to 600 metres. At 2am, the listening party ahead of 8 Platoon observed a large body of Chinese soldiers swarming through the gullies at about 700–800 metres moving from the pass. L/Nk Brij Lal, the leading party commander, ran back to platoon headquarters to inform this unusual development. He, along with his section commander, Nk Hukam Chand, and one LMG were rushed as reinforcement to the post.

By then, the Chinese had advanced within firing range of small arms from the post. The leading party fired a predetermined red “Very” light signal along with long bursts of LMG fire, warning the Charlie Company to “stand to” in their dug-out positions.

Similarly, the 7 Platoon’s listening position on the forward slopes also saw Chinese forming up. They promptly alerted the entire Charlie Company. Maj Shaitan Singh immediately contacted his sub-unit commanders on the radio. They confirmed that all ranks were ready in their battle positions. Since the paucity of troops had caused wide gaps between the positions of the 7 Platoon and the 9 Platoon, he also ordered the 9 Platoon to send a patrol to ascertain the situation. The patrol confirmed that a massive Chinese build-up had taken place through the gullies.

All ranks of the Charlie Company with their fingers on triggers, waited patiently for the impending major frontal attack on their positions around first light with improving visibility.

Around 5am, the first wave of the Chinese soldiers was spotted through the personal weapon sights by every troop in Maj Shaitan Singh’s Charlie Company manning the defences. And they greeted the enemy with a hail of LMG, MMG, and mortar fire.

Scores of Chinese troops were killed and many more were wounded. However, those who survived were promptly reinforced and they continued to advance. Soon all the gullies leading to Rezang-la were full of Chinese corpses.

In wave after wave, the Chinese launched four more attacks but were beaten back. However, the Indian troops also were facing manpower and ammunition shortage as several troops fell amid the relentless firing. As the fifth attack was launched, Nk Singh Ram, who was a wrestler of repute, led his comrades with a bayonet charge killing 6–7 Chinese troops singlehandedly until he fell.

By around 5.45am, the Chinese frontal attack failed, and they were beaten back.

Map of Rezang-la showing Indian positions on November 18, 1962. (By Jai Samota.)

Map of Rezang-la showing Indian positions on November 18, 1962. (By Jai Samota.)

After the setback, the Chinese realized that Rezang-la would not be a cakewalk for them and they changed their tactics. They began pounding Rezang-la with heavy artillery shelling. To destroy the Indian field fortifications, they used concentrated fire with 75mm recoilless (RCL) guns, which they brought on wheelbarrows from the flanks, and 132mm rockets.

The Chinese shelling was a spectacular display of firepower against the Indian defenders who had no artillery support and no bunker on the Rezang-la feature. In the thick of the battle, Maj Shaitan Singh was hit by enemy bullets in his arm. However, without caring for his own safety, he continued to fight.

The Chinese started regrouping for a rear attack on 7 Platoon positions that had no survivors. A little distance away, Nk Sahi Ram, the only survivor detached from his platoon, waited for the enemy to assemble and assaulted them with accurate LMG fire. The Chinese dispersed and Nk Ram waited for the next wave. It came, but with RCL guns, and blasted his lone firing position.

Maj Shaitan Singh regrouped his dwindling assets to charge the advancing Chinese. Since all the platoon positions had been overrun with no survivors, the enemy was regrouping to assault the Charlie Company headquarters from the rear after heavy pounding. While moving from one gun position to another, motivating his men, a burst of fire also hit Maj Shaitan in the abdomen. The remaining two men – CQMH Jai Narain and Hav Phool Singh – picked him up and continued to rush downhill towards the company base while taking cover behind boulders every now and then to escape the Chinese fire.

Maj Shaitan Singh had become unconscious with the loss of blood. He was rapidly turning cold. However, he regained consciousness for a moment and turned to his loyal men, who were risking their lives in trying to carry him and said that they should leave him alone and save their lives.

Reluctantly the men obeyed. According to the survivors, the fallen major’s last words were: “Tell the CO (commanding officer) and the battalion how well the company fought.” The snowy pinnacles of Rezang-la had stood helplessly by watching this unequal match of “so few against so many”.

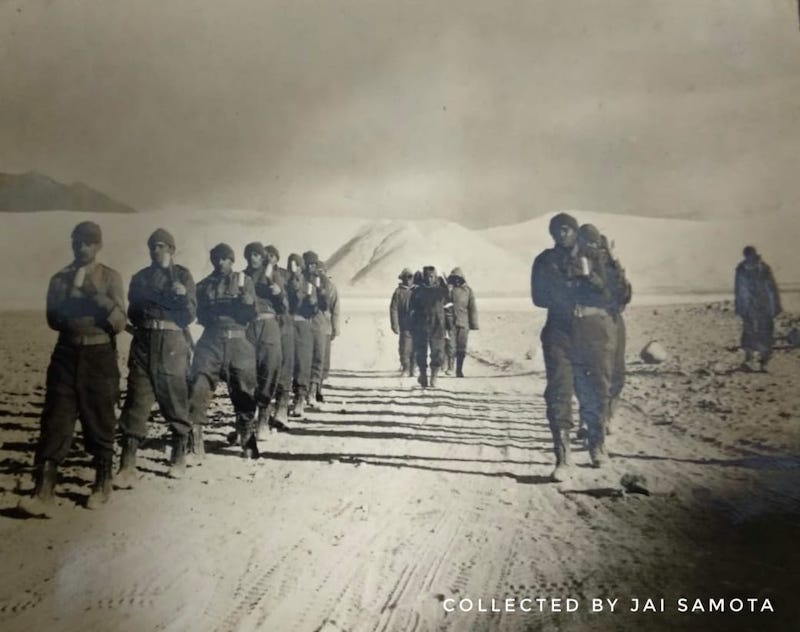

Indian soldiers giving a guard of honour to the mortal remains of Maj Shaitan Singh in Chushul, in February 1963. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

Indian soldiers giving a guard of honour to the mortal remains of Maj Shaitan Singh in Chushul, in February 1963. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

It was all over by about 9am.

Company Hav Maj Harphool Singh led three survivors to fight and stop the enemy’s onslaught until they fell. Ram Kumar’s 3-inch mortar section having used all its ammunition was ordered to be disabled and the firing plans and maps destroyed lest they fall into Chinese hands. As Ram Kumar was disabling his mortars, he was hit by rifle fire from the Chinese from 20 yards away. Though wounded, he took position in his command post and as the Chinese peeped in, he pumped bullets with his bolt-action .303 rifle and killed several of them.

The remaining Chinese hurled hand grenades to silence him and left. After many hours profusely bleeding, he regained consciousness and painfully trekked back to the battalion headquarters to narrate the chilling, gallant untold story of the Battle of Rezang-la.

Silence of war engulfed Rezang-la as the last round had been fired and the last soldier bled to eternal glory. Neither any help or reinforcements were asked for nor could any be provided to the Charlie Company.

Charlie Company’s soldiers kept their promise of fighting until the last bullet and the last breath. Out of a total of 127 all ranks, one officer, two JCOs, and 105 other ranks were killed in action. One JCO and 4 other ranks were taken prisoner. Of the five prisoners, one later succumbed to his wounds. Only four managed to return alive from the hellfire of Rezang-la, on November 18.

It is said that the battle had only 17 Survivors.

The Battle of Gurung Hill

Gurung Hill was also a significant feature. It measured 3,000 metres in length, 2,000 metres in breadth, and 5,030 metres in height. This feature was strategically important since it overlooked both the airstrip and the Spanggur Gap. On its northern flank is Black Top, which was occupied by the Chinese and had infantry on its reverse slope. The Chinese also had an artillery observation position on Black Top from which they could readily monitor Indian activity at Gurung Hill.

The hill is divided into two sections, one of which resembles a camel’s back, thus giving it the name “Camel’s Back” and the other a flat top, which gives it the name “Table Top”.

Map of Gurung Hill on November November 18 and 19, 1962. (By Jai Samota.)

Map of Gurung Hill on November November 18 and 19, 1962. (By Jai Samota.)

The 1/8 GR unit deployed its Bravo Company’s lesser platoon at the Table Top and a platoon at Camel’s Back. 2/Lt Shyamal Dev Goswami and his three soldiers manned the Indian artillery observation position on the hill. Gurung Hill was adequately backed by artillery as well as tanks, which were primarily inducted to confront enemy tanks at Spanggur Gap proved to be beneficial.

On November 18, Chinese heavy artillery and mortar fire pounded Gurung Hill, as well as all other features. In Gurung Hill, the enemy bombardment was less successful than at Rezang-la.

Attack on Table Top

The Chinese infantry troops, numbering hundreds, began to advance from Black Top towards the Table Top. The Gorkhas were waiting for the enemy to get within their firing range when artillery operator 2/Lt Goswami, who had been sent to relieve Capt AD Singh* for only a day or two, got involved in the battle and was given a higher level of responsibility.

He kept bringing accurate fire to the Chinese. This effectively prevented the Chinese from advancing because Indian artillery fire succeeded in killing many of their troops.

Instantly the Gorkhas began shooting at the enemy with their single-shot weapons, thwarting at least two enemy attacks from the Black Top, but the platoon’s front section was quickly overrun. Capt Purshottam Lal Kher, the post commander, kept moving from post to post in the face of enemy shelling until he was severely wounded. As Capt Kher got wounded, Jem Tej Bahadur Gurung took over the leadership and continued battling and repelling the enemy. And when the enemy struck in waves, he moved from post to post repelling each enemy onslaught.

The fierce battle raged on for several hours, with the enemy suffering severe casualties. Jemadar Tej Bahadur was wounded in the chest by a burst of fire while moving from one position to another, but he refused to be evacuated and fell fighting.

Then Capt Kher ordered the Gorkhas to withdraw since they were outnumbered. Capt Kher requested artillery support on his own position to cover the retreat. To cover the withdrawal, the tanks also provided direct fire.

The Gorkhas fought valiantly at the Table Top, but it was overwhelmed by 10pm. 2/Lt Goswami was severely wounded while bringing artillery fire on the enemy. His face was half blown off, and his TA Gurdeep, who took charge when the officer was wounded, was shot dead on the spot along with the two signallers, TA Pritam Singh and TA Sarwan Singh.

Despite his injuries and heavy bleeding, 2/Lt Goswami grabbed his radio and screamed “fire till eternity” to his battery of guns.

He collapsed shortly after issuing this instruction.

Read also: ‘Fire Till Eternity’: The story of Maj Shyamal Dev Goswami

Later, the Chinese arrived at his post to look for survivors in the area where Second Lieutenant Goswami laid in excruciating pain. Fortunately for him, they assumed he was dead and abandoned the post. The young officer regained consciousness a day later and crawled and limped towards the base when two Gorkha soldiers spotted him and carried him to give him medical assistance. He was declared dead, but there was a movement in his body, and he was quickly evacuated and sent to the Military Hospital in Delhi.

With the fall of Rezang-la, there was a threat of an attack on the Chushul-Dungti track. The commanding officer of 13 Kumaon discussed the threat of an attack during the night with the brigade commander, and the brigade commander decided to send one tank troop at last light, which will return to its hiding position by first light. Lt Avinash Chand arrived at 13 Kumaon’s headquarters just before dusk with one troop without a tank. He left the troop there and returned to repair the stalled tank. Lt Chand returned to the re-entrant and reported that there had been no Chinese activity in the region all throughout the night.

The attack on Camel’s Back

Due to precise artillery barrage, the Chinese sustained high fatalities at Table Top. They did not attack until the afternoon of November 19, but they kept firing artillery, to which our tanks and guns responded fiercely. However, due to the absence of the trained operators, the fire wasn’t precise. At around 8.30pm, the Camel’s Back was attacked from two sides – one from the Table Top, a former Gorkha position, and the other from the Spanggur Gap.

The Chinese intensified their two-pronged onslaught on the Indian platoon position, making it impossible for our troops to resist against them. The Chinese overran the position at the Camel’s Back in less than an hour. The enemy suffered huge casualties, but the Gorkhas also suffered several casualties. Out of 102 all ranks, 26 were killed in action and several others wounded.

The battle of Gurung Hill was over.

After the fall of Gurung Hill to the Chinese, the Indian Air Force aircraft could no longer land on the airfield for risk of being severely damaged by the enemy.

Magar Hill

The post and the battalion headquarters had lost touch with Rezang-la, so Maj Jatar sent a four-man patrol led by an NCO to investigate what had occurred there. Nonetheless, the Chinese surrounded the patrol and killed two men before they reached Rezang-la. The remaining two men, however, managed to escape and reach their company position.

During the Battle of Gurung Hill, Indian artillery fired constantly, but the enemy soldiers did not approach the Magar Hill stronghold although they mercilessly bombarded the post. The Magar Hill also possessed artillery operators, but no operator officer was present during the battle. The post commander, Major Jatar, did the job himself and directed artillery fire on the enemy in the immediate vicinity and the Spanggur Gap.

During the whole battle, the artillery fired more than 2,700 rounds.

The aftermath

On the evening of November 19, troops from the 114 Brigade began to retreat from their positions, and by first light, all units had established depth positions in allotted locations.

At Tsaka-la, Alpha Company of 5 Jat retreated to Dungti to join the 70 Infantry Brigade. Except for two RCL guns and two tanks that were damaged during the bombardment, all equipment was shifted.

On November 21, the Chinese announced a ceasefire. Later, the whole brigade withdrew, and a vehicle convoy with supplies and weaponry was dispatched to Leh. The brigade suffered 140 fatalities of all ranks in the Battle of Chushul, compared to the 1,000-plus casualties the Chinese sustained.

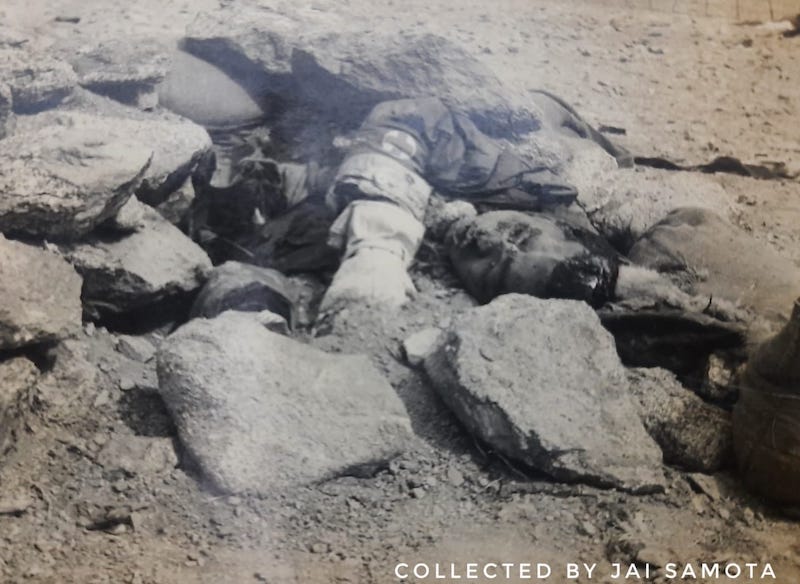

In February 1963, after the India-China war was over, a native Ladakhi shepherd wandered across the Rezang-la feature. He was astounded by the incredible battle spectacle of warriors’ frozen bodies but still clutching their wrecked weapons. Their firearms were mostly empty and had bulging barrels from repeated shooting.

A week later, in February 1963, the first Indian party of the International Red Cross and Indian Army reached Rezang-la and discovered 97 corpses in the shattered trenches with various splinters and bullet wounds. The frozen body of Nk Dharampal Dhaiya, a nursing assistant, was holding a morphine syringe and a bandage. Maj Shaitan Singh’s body was discovered near where he was last seen by his two men.

Body of nursing assistant Nk Dharampal Dhaiya with a syringe and bandage in his hand. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

Body of nursing assistant Nk Dharampal Dhaiya with a syringe and bandage in his hand. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

Of the 97 bodies of the fallen soldiers that were discovered, 96 were cremated at the Chushul High Ground where the battalion headquarters used to be. Maj Shaitan Singh’s mortal remains were sent to Jodhpur.

Maj Shaitan Singh’s funeral procession in Jodhpur. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

Maj Shaitan Singh’s funeral procession in Jodhpur. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

In the Gurung Hill area, 26 bodies of fallen soldiers were found. Maj Dhan Singh Thapa and other 5 Jat and 13 Kumaon prisoners of war were repatriated to India in May 1963.

Maj Thapa and Maj Shaitan Singh were both awarded the Param Vir Chakra for their exceptional valour and commitment to service. Brig Tapishwar Narain Raina, 2/Lt Shyamal Dev Goswami, who lost both legs to frostbite, and Nk Rabi Lal Thapa received the Maha Vir Chakra. Lieutenant Colonel HS Dhingra received the Ati Vishisht Seva Medal for his commitment to duty throughout the conflict.

Sqn Ldr Chandan Singh of the Indian Air Force, Capt Ashwani Kumar Dewan of 20 Lancers, Capt PL Kher and Sub Amar Bahadur Gurung of 1/8 GR, TA Gurdip Singh of 38 Field Battalion along with Nk Gulab Singh, L/Nk Singh Ram, Nb Sub Surja Ram, Nk Hukam Chand, NA Dharampal Dahiya, Jem Hariram Yadav and Jem Ram Chander Yadav, Hav Ram Kumar of 13 Kumaon were awarded Vir Chakra.

Photo taken during the inauguration of the Rezang-la War Memorial and the raising day of 13 Kumaon, on August 5, 1963. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

Photo taken during the inauguration of the Rezang-la War Memorial and the raising day of 13 Kumaon, on August 5, 1963. (Photo collected by Jai Samota through special arrangement.)

Two memorials were erected, one at the cremation place of 13 Kumaon to memorialize the courageous souls of Rezang-la, and the other near the Chushul village to honour the valiant Gorkhas and Gunners.

“To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his Gods.”

~ Thomas Babington Macaulay, “Lays of Ancient Rome”.

This is dedicated to the braves who stared in the eyes of death and made the supreme sacrifice with their lives defending the motherland in Ladakh in the 1962 war.

*The full names are not available with either the author or India Sentinels. If any reader is aware of the names, he/she is requested to assist us by sending the names to [email protected].

Short forms guide:.

Maj Gen: Major general

Brig: Brigadier

Col: Colonel

Lt Col: Lieutenant colonel

Maj: Major

Sqn Ldr: Squadron leader

Capt: Captain

Lt: Lieutenant

2/Lt: Second lieutenant

Sub: Subedar

Nb Sub: Naib subedar

Jem: Jemadar

CQMH: Company quartermaster havildar

Hav: Havildar

Nk: Naik

L/Nk: Lance naik

TA: Technical assistant

NA: Nursing assistant

2IC: Second in command

GR: Gorkha Rifles

PVC: Param Vir Chakra

MVC: Maha Vir Chakra

VrC: Vir Chakra

MC: Military Cross

AVSM: Ati Vishisht Seva Medal

LMG: Light machine gun

MMG: Medium machine gun

References:

The writer has interviewed/spoken to and got inputs from the following people:

1. Magar Hill post commander Brig RV Jatar

2. Gurung Hill company commander Maj Gen PL Kher, VrC

3. Artillery commander Brig SP Joshi

4. Tank squadron Commander Maj Gen AK Dewan, VrC

5. Tsaka-la company commander Col Prem Singh

6. Initially company commander at Rezang-la Brig Prem Kumar

7. Quartermaster 1 JATLI Colonel SP Dua

8. Adjutant 1 Jat Light Infantry Brig KS Kang

9. Bravo Company commander 1 Jat Light Infantry Brig SS Kaler

10. Tank commander Brig Balbir “Spanner” Sandhu

11. 5 Jat Sub Balwant Singh (who lost his leg in a Chushul mine blast.)

12. 13 Kumaon Honorary Capt Ram Chander Yadav

13. 13 Kumaon Hav Nihal Singh

14. 13 Kumaon Hav Asha Ram

15. 13 Kumaon Hav Sahi Ram

16. Family of Maj Shaitan Singh, PVC

17. Family of Lt Col DS Thapa, PVC

18. Family of Lt Col HS Dhingra, AVSM

19. Son of Lt Col Bakhtawar Singh CO 5 Jat

20. Son of AVM Chandan Singh, MVC, AVSM, VrC

21. Sister of 2/Lt (later Maj) SD Goswami, MVC

22. Wife of Lt (later Maj) Avinash Chand of 20 Lancers

23. Wife of Lt (later Maj) PM Wakhle of 13 Kumaon

Books:

1. “The Saga of Ladakh” by Maj Gen Jagjit Singh

2. “Lest We Forget” by Capt Amarinder Singh

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect the views of India Sentinels.

Follow us on social media for quick updates, new photos, videos, and more

Twitter: https://twitter.com/indiasentinels

Facebook: https://facebook.com/indiasentinels

Instagram: https://instagram.com/indiasentinels

YouTube: https://youtube.com/indiasentinels

© India Sentinels 2022-23