BSF troops patrol along a border fence between India and Bangladesh in West Bengal. (File photo)

BSF troops patrol along a border fence between India and Bangladesh in West Bengal. (File photo)

The chief minister of West Bengal, Mamata Banerjee, made a calculated intervention during a state assembly discussion on the governor’s address on February 5. While expressing her government’s willingness to provide land for border fencing – a critical national security requirement – she attached two conditions that have ignited a fresh debate on Centre-state relations and border security priorities.

Banerjee demanded that the Union government first complete pending fencing work on land already provided by her administration. More controversially, she insisted on the rollback of what she termed an “arbitrary decision” to expand the Border Security Force’s (BSF) jurisdiction from 15km to 50km from the international boundary before her government would consider releasing additional land.

This response came amid allegations from the Centre and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party that the West Bengal government was obstructing border fencing by withholding land – a charge with serious implications for national security. The state has consistently opposed the jurisdiction expansion, characterizing it as an unconstitutional infringement on federalism and state police powers.

Read also: Why 8th pay panel must recognize CAPF personnel as true soldiers

A National Vulnerability

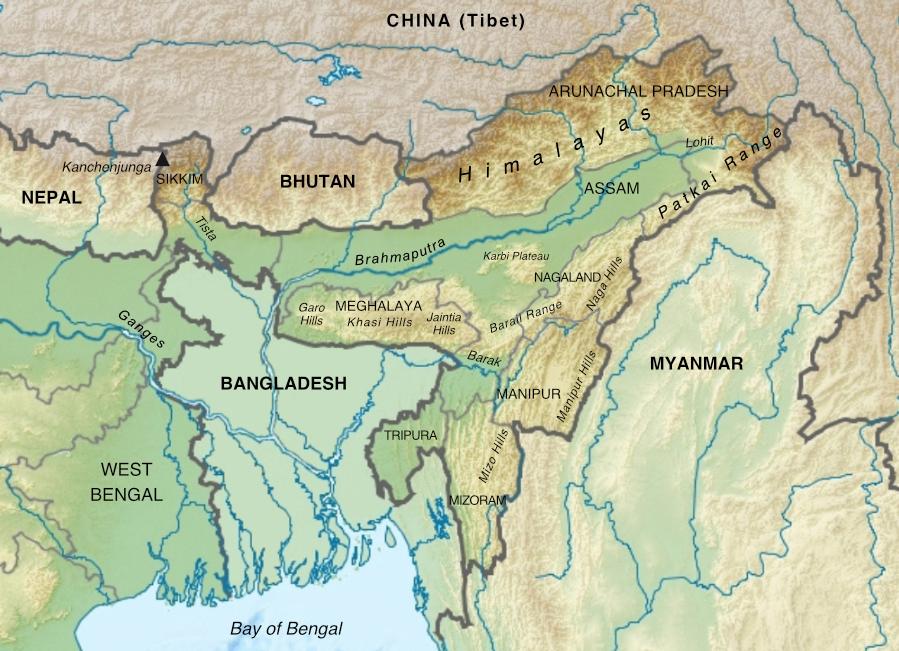

India shares 4,096.7km of border with Bangladesh. According to the minister of state for home affairs, Nityanand Rai, responding to Lok Sabha unstarred question no. 1175 on February 11, 2025, approximately 864.482km of this border remains unfenced. This figure includes 174.514km classified as “non-feasible gaps” due to challenging terrain such as marshlands and landslide-prone areas, objections from the Border Guards Bangladesh, limited working seasons, and delays in land acquisition.

In reality, roughly 689.968km – approximately 16.84 per cent of the India-Bangladesh border – remains genuinely unfenced and vulnerable to illegal crossings. This is not merely a statistical concern; it represents a significant security gap that demands urgent attention.

The situation in West Bengal is particularly acute. In response to Rajya Sabha unstarred Question No. 3044 on August 20, 2025, Rai revealed that of the state’s 2,216.7km border with Bangladesh, 1,647.696km is fenced, leaving 569.004km uncovered. Of this unfenced stretch, 112.780km is classified as non-feasible, while 456.224km is feasible for fencing.

The data becomes more troubling upon closer examination. Of the 456.224km feasible length in West Bengal, land for only 77.935km has been handed over to the executing agency. For the remaining 378.289km, land acquisition has not even been initiated for 148.971km, while the balance is at various stages of acquisition. This means over 20 per cent of West Bengal’s Bangladesh border remains unfenced – a harsh reality that underscores the need for the Centre to invoke essential provisions of national security to expedite land acquisition.

Read also: Bangladesh in Turmoil – Why BSF must abandon non-lethal tactics now

Rather than focusing resources and political capital on completing this critical infrastructure, the government has chosen to expand BSF jurisdiction – a move that appears more symbolic than substantive in addressing the core problem of infiltration and illegal immigration.

Controversial Jurisdictional Expansion

In October 2021, the Ministry of Home Affairs invoked section 139 of the BSF Act 1968, allowing BSF officers to conduct search, seizure, and arrest operations within 50km of the international boundary in Punjab, Assam, and West Bengal. Previously, this jurisdiction extended only 15km into these states, while it was 50km in Rajasthan and 80km in Gujarat.

The Punjab government challenged this notification in the Supreme Court, terming it unconstitutional and violative of federal structure. Punjab argued that the decision encroached upon the state’s legislative domain and police powers, effectively extending borders 50km into sovereign state territory and compromising exclusive state powers regarding law and order.

While Assam welcomed the move as supporting national security, both Punjab and West Bengal opposed it vigorously, passing resolutions in their state assemblies against the expansion. This divergence in state responses itself suggests that the policy may not have been adequately consultative or sensitive to federal concerns.

Read also: Radicalization is a national crisis that demands constitutional resolve

Professional Security Assessment

An honest professional analysis raises fundamental questions about whether the security situation actually warranted this jurisdictional expansion. Unlike the line of actual control (LAC) in eastern Ladakh, which has seen genuine instability and unpredictability, the security situation along the borders affected by the jurisdictional change was stable and normal. The BSF was effectively guarding these borders, and there was no declared security alarm requiring emergency measures.

According to media reports, the-then BSF director general, Pankaj Singh, addressed reporters and provided revealing insights into the rationale. “One of the reasons to extend the jurisdiction of BSF up to 50km in border states was the demographic change in Assam and West Bengal,” he stated. “We have the district-wise composition of how the demography has changed in these areas.”

Singh continued: “Infiltration is a big issue, due to which Tripura and Assam witnessed agitation, and in Bengal, demographic imbalance has happened in several districts.” He clarified that the BSF’s jurisdiction had primarily been extended regarding powers under the Passport Act and the Passport (Entry into India) Act, specifically targeting those violating border entry rules.

Read also: Fighting White-Collar Terror – India’s battle begins in the classroom

This statement by the director general is, inadvertently, an acknowledgment of the BSF’s inability to completely seal the border despite it being their primary mandate. This could be attributed to various factors – most prominently the porosity of the border itself and frequent redeployment of BSF personnel from the eastern border to meet miscellaneous deployment needs elsewhere.

The reasoning provided clearly points to the fact that what the BSF actually needs is greater investment in establishing an effective surveillance grid – a hybrid model combining boots on the ground to maintain vigilant watch over the stretch between the international boundary, the fence, and the border road to prevent infiltration. Based on terrain-specific requirements, the BSF needs to strengthen its surveillance capabilities for border security, which remain inadequate except on a few stretches along the western border. It is this fundamental failure that has perhaps contributed to demographic imbalances, not insufficient jurisdictional reach.

Read also: SC judgment on CAPF officers is final. Implementation must begin

Federal Question

In arguments before the Supreme Court, the government maintained that extending jurisdiction falls within the scope of the BSF Act and submitted that the extension was intended to bring uniformity in jurisdiction across border states. Notably absent from this reasoning was any mention of an urgent security need for the extension – which should ideally have been the primary consideration for increasing jurisdiction.

Equally troubling is the apparent lack of consultation with affected state governments, as envisaged and expected under India’s federal structure. This unilateral approach has damaged centre-state trust precisely when cooperation is most needed for national security.

What emerges clearly is that the expansion of jurisdiction does not appear connected to immediate border security needs or the challenge of detecting and deporting illegal immigrants. In the four-plus years since the notification, there has been little visible movement to enhance and strengthen BSF capabilities for operating in the hinterland up to 50km. There is no evidence of additional BSF battalions being raised or necessary setup established for executing this expanded mandate, nor of standard operating procedures being developed for how the force would coordinate with state police to check, detect, and deport illegal immigrants or infiltrators.

As matters stand, BSF capability is barely sufficient to guard the international boundary/unfenced borders and contiguous depth areas as dictated by terrain conditions. Expanding jurisdiction without commensurate capability enhancement appears more performative than practical.

Read also: Democratic Dilemma – How elections compromise border security

Logic of Differentiation

Applying logical reasoning, the increased jurisdiction – especially for Punjab, West Bengal, and Assam – is unlikely to meet security imperatives for detecting illegal immigrants. Rather, it risks creating federal conflict and fostering insecurity and distrust between civilians and the BSF, thereby negatively impacting border security itself.

The original logic for maintaining jurisdictional distance at 15km in Punjab, West Bengal, and Assam was sound. Population density in West Bengal and Assam is exceptionally high. Border management even within 15km is a herculean task given limited capabilities. It is extraordinarily difficult for the BSF, capability-wise, to keep even this 15km area under close surveillance while managing its primary responsibility of preventing cross-border crimes.

Currently, the BSF operates within the 15km depth zone after informing local police. There have been instances in the past where BSF personnel became entangled in legal issues precisely because they operated within their jurisdictional limits without taking police into confidence. Expanding this fraught relationship to 50km without addressing underlying coordination challenges is a recipe for conflict.

Read also: Ladakh Unrest – When promises meet reality on India’s strategic frontier

In Punjab, a 50km jurisdiction covers areas extending to most district headquarters and beyond, encompassing major cities such as Amritsar, Gurdaspur, Pathankot, Fazilka, and Abohar. This is almost certain to provoke federal conflict and create law enforcement confusion in densely populated urban centres.

Jurisdictional expansion must be influenced by realistic, ground-specific factors – not by bureaucratic uniformity that overrides terrain and demographic considerations. Any such expansion must be based on terrain configuration, population density, actual security requirements, and the reach of civil administration and police.

Path Ahead

Uniformity cannot be logical reasoning for increasing jurisdiction when security dynamics vary so dramatically across different border regions. There is a compelling case to roll back to the original jurisdiction of 80km for Gujarat, 50km for Rajasthan, and 15km for Punjab, Assam, and West Bengal – norms that were based on careful security analysis rather than administrative convenience.

Read also: My Identity Crisis – The CAPF soldier’s perennial dilemma

In the interest of federal harmony and practical security outcomes, the Union government should reconsider its position and return to jurisdictional norms grounded in terrain-specific security requirements. More importantly, it should redirect its focus and resources toward the urgent need to accelerate land acquisition for completing border fencing.

The reality is stark: nearly 690km of the India-Bangladesh border remains unfenced. This physical gap in our border infrastructure represents a far more immediate and tangible security vulnerability than any perceived benefit from expanded BSF jurisdiction. A fence, properly constructed and maintained, provides 24-hour deterrence. An expanded jurisdiction without the personnel, infrastructure, or standard operating procedures to make it effective provides little more than political optics.

Read also: Beyond Fencing – Complex reality of India’s most vulnerable border

It is incumbent upon both the Union government and state governments to cooperate with each other in the national security interest. This cooperation, however, must be premised on genuine consultation, respect for federal principles, and a clear-eyed focus on what actually enhances security rather than what merely appears to do so.

The choice before policymakers is clear: invest in completing the physical infrastructure that actually prevents infiltration or continue with jurisdictional expansion that risks alienating state governments and local populations without demonstrably improving security outcomes. National security demands we choose the former.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect the views of India Sentinels.

Follow us on social media for quick updates, new photos, videos, and more.

X: https://twitter.com/indiasentinels

Facebook: https://facebook.com/indiasentinels

Instagram: https://instagram.com/indiasentinels

YouTube: https://youtube.com/indiasentinels

© India Sentinels 2025-26